Actualités

L'actualité astronomique à l'Observatoire de Genève

Avenir «exoplanétaire» lumineux pour l’Université de Genève

Le ciel profond livre de nouveaux secrets

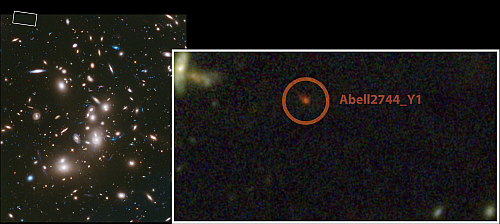

Même les galaxies les plus lointaines n’échappent plus à l’œil des astronomes. Grâce à de nouvelles images des télescopes spatiaux Hubble et Spitzer, le processus de formation des galaxies est de mieux en mieux connu. Une équipe de l’EPFL et de l’Université de Genève, associée à des chercheurs français, américains et espagnols, livre ses premières conclusions.

Image de la galaxie lointaine, appelée Y1, découverte derrrière l'amas de galaxies Abell 2744. Le redshift photométrique de la galaxie et z~8.0, indiquant qu'elle se situe à environ 13 milliard d'annéees lumière. La galaxie est ainsi vue comme elle était environ 650 millions d'années après le Big Bang.

http://obswww.unige.ch/Research/starburst/

http://obswww.unige.ch/Research/starburst/pr_ff2014.html

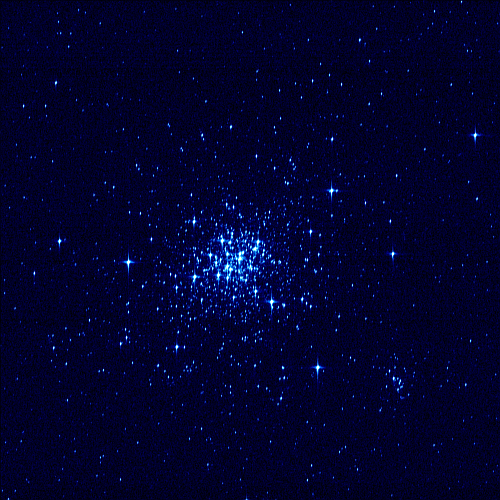

Gaia comes into focus

ESA’s billion-star surveyor Gaia is slowly being brought into focus. This test image shows a dense cluster of stars in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a satellite galaxy of our Milky Way.

Once Gaia starts making routine measurements, it will generate truly enormous amounts of data. To maximise the key science of the mission, only small ‘cut-outs’ centred on each of the stars it detects will be sent back to Earth for analysis.

This test picture, taken as part of commissioning the mission to ‘fine tune’ the behaviour of the instruments, is one of the first proper ‘images’ to be seen from Gaia, but ironically, it will also be one of the last.

Gaia was launched on 19 December 2013, and is orbiting around a virtual point in space called L2, 1.5 million kilometres from Earth.

Gaia’s goal is to create the most accurate map yet of the Milky Way. It will make precise measurements of the positions and motions of about 1% of the total population of roughly 100 billion stars in our home Galaxy to help answer questions about its origin and evolution.

Repeatedly scanning the sky, Gaia will observe each of its billion stars an average of 70 times each over five years. In addition to positions and motions, Gaia will also measure key physical properties of each star, including its brightness, temperature and chemical composition.

To achieve its goal, Gaia will spin slowly, sweeping its two telescopes across the entire sky and focusing the light from their separate fields simultaneously onto a single digital camera – the largest ever flown in space, with nearly a billion pixels.

But first, the telescopes must be aligned and focused, along with precise calibration of the instruments, a painstaking procedure that will take several months before Gaia is ready to enter its five-year operational phase.

As part of that process, the Gaia team have been using a test mode to download sections of data from the camera, including this image of NGC1818, a young star cluster in the Large Magellanic Cloud. The image covers an area less than 1% of the full Gaia field of view.

The team is making good progress, but there is still work to be done to understand the full behaviour and performance of the instruments.

While all one billion of Gaia’s target stars will have been observed during the first six months of operations, repeated observations over five years will be needed to measure their tiny movements to allow astronomers to determine their distances and motions through space.

As a result, Gaia’s final catalogue will not be released until three years after the end of the nominal five-year mission. Intermediate data releases will be made, however, and if rapidly changing objects such as supernovae are detected, alerts will be released within hours of data processing.

Eventually, the Gaia data archive will exceed a million Gigabytes, equivalent to about 200 000 DVDs of data. The task of producing this colossal treasure trove of data for the scientific community lies with the Gaia Data Processing and Analysis Consortium, comprising more than 400 individuals at institutes across Europe (18 scientists/software engineers being from the University of Geneva).

Gaia calibration image of the young star cluster NGC1818

Long: A Gaia test image of the young star cluster NGC1818 in the Large Magellanic Cloud, taken as part of calibration and testing before the science phase of the mission begins. The field-of-view is 212 x 212 arcseconds and the image is approximately oriented with north up and east left. The integration time of the image was 2.85 seconds and the image covers an area less than 1% of the full Gaia field of view.

Gaia’s overall design is optimised for making precise position measurements and the primary mirrors of its twin telescopes are rectangular rather than round. To best match the images delivered by the telescopes, the pixels in Gaia’s focal plane detectors are then also rectangular. In order to produce this image of NGC1818, the image has been resampled onto square pixels. Furthermore, to maximise its sensitivity to very faint stars, Gaia’s main camera does not use filters and provides wide-band intensity data, not true-colour images. The false-colour scheme used here relates to intensity only. The real colours and spectral properties of the stars are measured by other Gaia instruments.

Credits: ESA/DPAC/Airbus DS

http://cosmos.esa.int/web/gaia

http://www.isdc.unige.ch/Gaia/

http://obswww.unige.ch/Research/variability/

Le projet « PlanetS » a été sélectionné par la Confédération comme Pôle de recherche national (PRN). Ce vaste programme de recherche vise à déchiffrer l'origine et l'évolution des planètes.

Les récents progrès scientifiques dans le domaine de la planétologie marquent le tournant d'une ère de découverte des exoplanètes à celle de la caractérisation physique et chimique de ces nouveaux mondes du cosmos. Dans ce cadre, les activités de recherche du PRN PlanetS s'aligneront sur trois principaux thèmes scientifiques : l'origine, l'évolution et la caractérisation des planètes en particulier et des systèmes planétaires dans leur ensemble. En combinant les observations astronomiques, l'étude de la Terre et des corps du Système solaire par les sondes spatiales, les mesures de laboratoire et la modélisation théorique, ces activités catalyseront un changement dans l'ampleur et la portée de la recherche menée en Suisse dans ce domaine phare de l’astrophysique moderne.

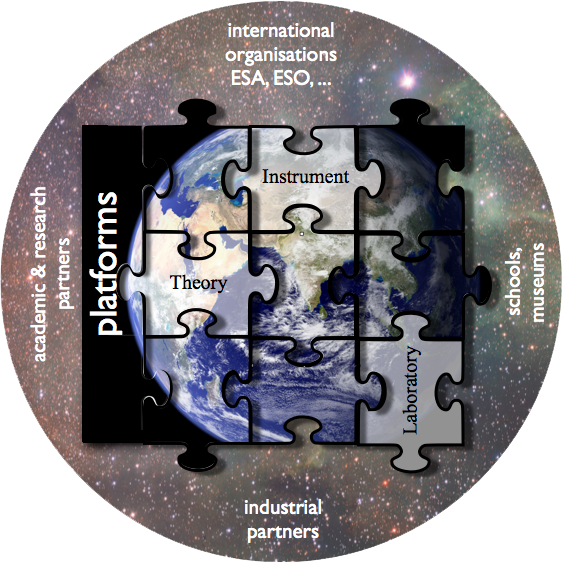

L'organisation de PlanetS vise à un effet structurant au niveau suisse de toute la discipline. PlanetS va permettre de

1) créer un réseau de doctorat interdisciplinaire en sciences planétaires afin de coordonner la formation de jeunes scientifiques hautement qualifiés,

2) établir des plates-formes permettant le développement et le transfert technologique ainsi que les échanges et l'analyse des données,

3) assurer une bonne visibilité à l'exploitation scientifique des données du futur satellite CHEOPS de l’Agence Spatiale Européenne dont le développement est sous responsabilité suisse,

4) développer de nouveaux groupes de recherche et de nouvelles installations de laboratoire,

5) mener un vaste programme d'éducation et de sensibilisation multirégional.

Finalement, PlanetS va poser les bases d'un Institut suisse des sciences planétaires (SIPS) qui portera ces activités au-delà de la durée de vie du PRN.

Les universités de Berne et de Genève sont les deux principaux instituts menant le PRN PlanetS. Le directeur du NCCR est le professeur Willy Benz (Institut de physique de l'Université de Berne), le co-directeur est le professeur Stéphane Udry (Département d'astronomie de l'Université de Genève).

.