Blockbusters, 1.

Portraits and busts in abundance.

A chart of a male and super individualistic West?

Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel

Politicians, businessmen, writers, journalists, artists, academics...

This stock of images speaks first of all of those who have thought, oriented, and animated the activities of the world -and first of all of the so-called Western world.

Each portrait quotes in a simple way the iconographic tradition of the official portrait of kings or ministers: frontal face, bust portrait, direct look, tight lips.

These portraits are mostly portraits of men.

They appear in all types of magazines. The women's faces that appear in this cluster are almost always published in fashion or entertainment magazines, or in advertisements.

Is a portrait in the press at that time necessarily proof of a certain power?

The men seem stuck in an inextricable frame. They rarely smile.

Their silhouettes, omnipresent in the press of the 1900s and 1920s in particular, emerge from a past in which the male body is educated to immobility, both visual, bodily, social -and perhaps political immobility. This is not only due to the conditions of the photographic work: the portraits of women smile, turn around, raise their heads.

Photographic portraits of women more often involve the whole body.

They are mainly diffused in the advertising and entertainment sections: the female body is used mainly for advertising theaters, operas and soon cinemas, or to highlight clothing fashions -in other words, to arouse desire.

How much have we changed?

With images perhaps circulates a collective unconscious, as the art historian Aby Warburg pointed out more than a century ago.

Warburg was interested in the permanence of certain forms and images from one civilization to another; he studied the circulation of what he called formulas of pathos, the persistence of feelings, fears or expectations in the circulation of visible forms. Commenting on Warburg, the art historian Georges Didi-Huberman likes to translate this idea into a very telling image: the survival of ghosts.[1]

There are ghosts in these portraits.

Their omnipresent silhouettes give the impression of a past in which the male body was educated to immobility, both visually and socially. We will need to explore further how this tight arrangement of men (even more than women) has evolved over time and space.

After World War I, in film and theater magazines, photographs of men are more vivid.

The first clues appear as early as the 1910s. New technical possibilities may have played a role in this change: with the reduction of the pause time, and then the reduction of the size of the cameras, travel and reportage photography became possible. It was easier to capture the image of a moving body, and long pauses were no longer necessary.[2] Full-length portraits were also becoming more common, in which the male figure was represented in its entirety. The 1920s -the period of the development of small cameras such as the Leica- saw bodies come to life in our illustrated periodicals.

These are the années folles. Crazier, in any case, than the previous years. Have the ghosts vanished?

The woman, queen among the busts

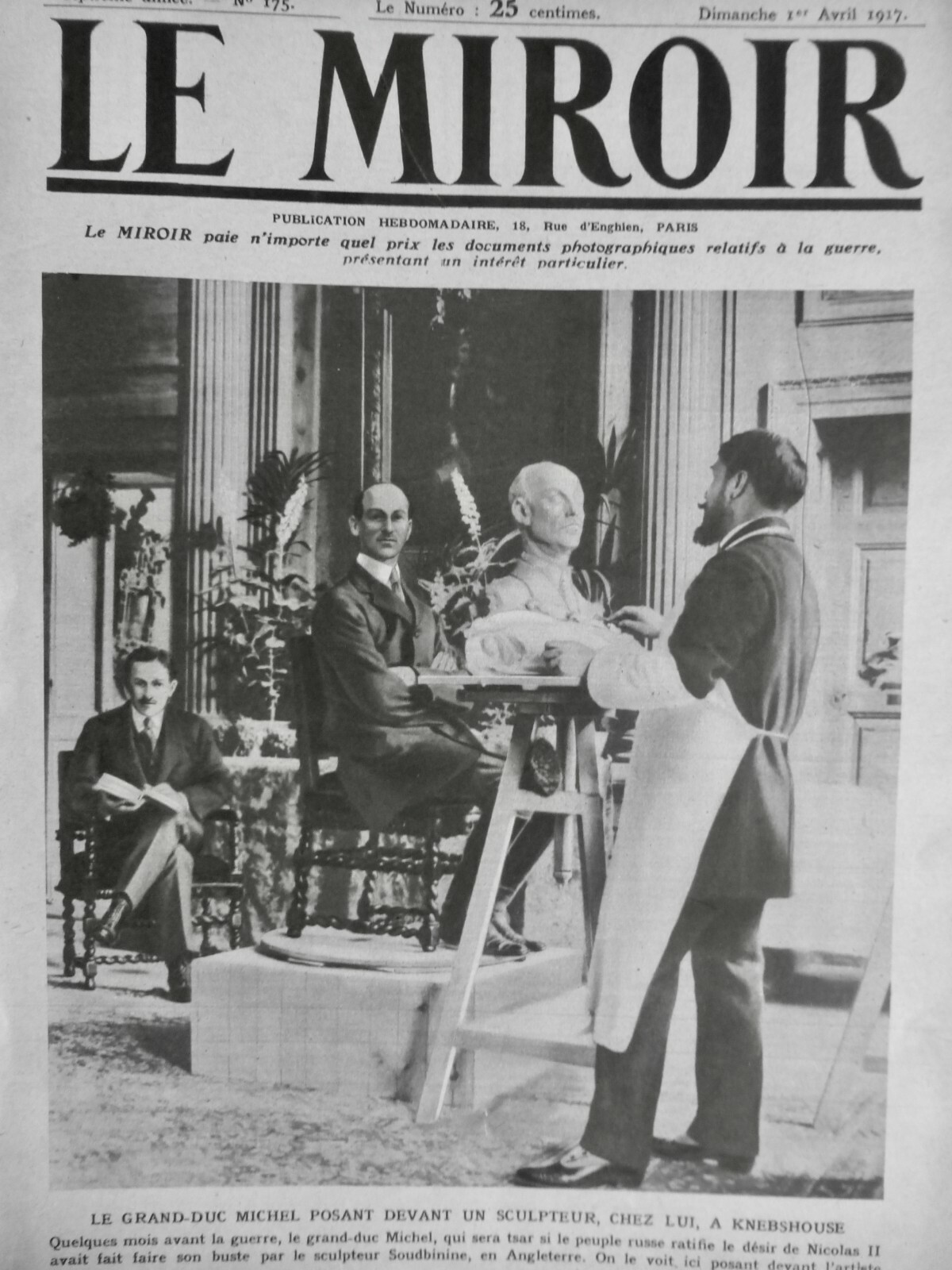

The relationship between men and women is no longer the same in the case of photographs of busts, also very common in our corpus.

Busts of women are more represented than those of men, especially around 1900, in the 1930s and 1940s. Busts of children also appear.

First image: Absolute frequency of busts in our corpus of 3 million images (women, men, children).

Hovering image: Relative frequency of the same busts in the corpus.

The recognition of the genre of portraits is very easy for this period.

The first graph (absolute frequency) is interesting because of the numbers it reveals -more than 300 images of busts for some years- but it remains misleading: if for some years we have many more images, don't we risk believing too quickly in evolutions which, relativized, are no longer so?

The graph displayed on mouse-over, where the relative frequencies of appearance of busts in our corpus of illustrated press are calculated, is more revealing. In order not to overestimate the frequency of bust photographs during periods when our general image corpus is larger, we have divided the total number of busts found by the algorithm by the total number of images retrieved for the year.

Rather than indicating a representation of the world in which men dominate, the strong presence of busts suggests modes of self-representation specific to an international European elite in which women played a role -patrons, salon women, muses, mothers...

The bust is not only a story of great men. It is at the beginning of the century a fashion which touches the women in the first place.

The elites like to have their figures immortalized, and the press regularly praises the result. In the satirical periodicals, some make fun of the middle classes who are unable to refuse the privilege of posing for a bust. The portrait sculptors were also mocked for taking advantage of the posing sessions of naïve young girls who were not very difficult to deflower.

Jean Veber (1868-1928), The Bust [photomechanical print], 1896. Source : Gallica (http://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb40462413b)

The busts were modeled according to an ancient aesthetic considered superior, inherited from Greece and Rome. The Europe of images of the first 20th century imitated the past.

Our fantasy, in the twenty-first century, is that we have long since left this past logic behind. But when did this change occur?

The publication of photos of busts in the press increases sharply in the 1920s and 1940s, then falls back quite sharply after the Second World War.

Thereafter, it hardly resumes. We will be interested in a later chapter [A short epidemiology of images, chapter VI] in the social and aesthetic reasons likely to illuminate these successive waves. But for the fall of the post-war period, the abrupt change of taste can manifest the sudden advent of a new political and geopolitical world order. Modernity imposes itself in visual practices after 1945, fascisms having recovered too much the heritage of the old empires for their benefit.[3] The reference to ancient practices is no longer relevant. Perhaps another relation to the world is also imposed then, where the idea of an individual as lord of the universe does not really have its place anymore.

--

Plato. Plaster. Collection des moulages de l'université de Genève. Photographer / 3D model: Davide Angheleddu 2019, Copyright 2021. Original: Copenhagen, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, inv no. I.N. 2553

Read more :

Christianity in the background. The case of the Virgin and Child

Chapter:

IV. Blockbusters

Références

[1] Georges Didi-Huberman, L'image survivante. L'histoire de l'art et le temps des fantômes (Paris: Minuit, 2002).

[2] Jean-Paul Gandolfo, "Photography - History of photographic processes", Universalis, https://www.universalis.fr/encyclopedie/photographie-histoire-des-procedes-photographiques/5-l-essor-des-systemes-argentiques-au-xxe-siecle/.

[3] Eric Michaud, Un art de l'éternité. L'image et le temps du national-socialisme (Paris: Gallimard, Folio Histoire, 2017). On the widespread abandonment of the aesthetics of the 1930s and 1940s, in favor of modern art and abstraction, see Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel, Naissance de l'art contemporain 1945-1970. Une histoire mondiale (Paris: CNRS Editions, 2021).