An epochal possibility: the digitized past

Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel & Nicola Carboni

In computational studies, the quality of the corpus is essential.

What are we working on?

Since the early 2000s, numerous archives, libraries, museums and universities have digitized and put online millions of pages of illustrated prints, photographs, posters and works of art produced and circulating throughout the world.

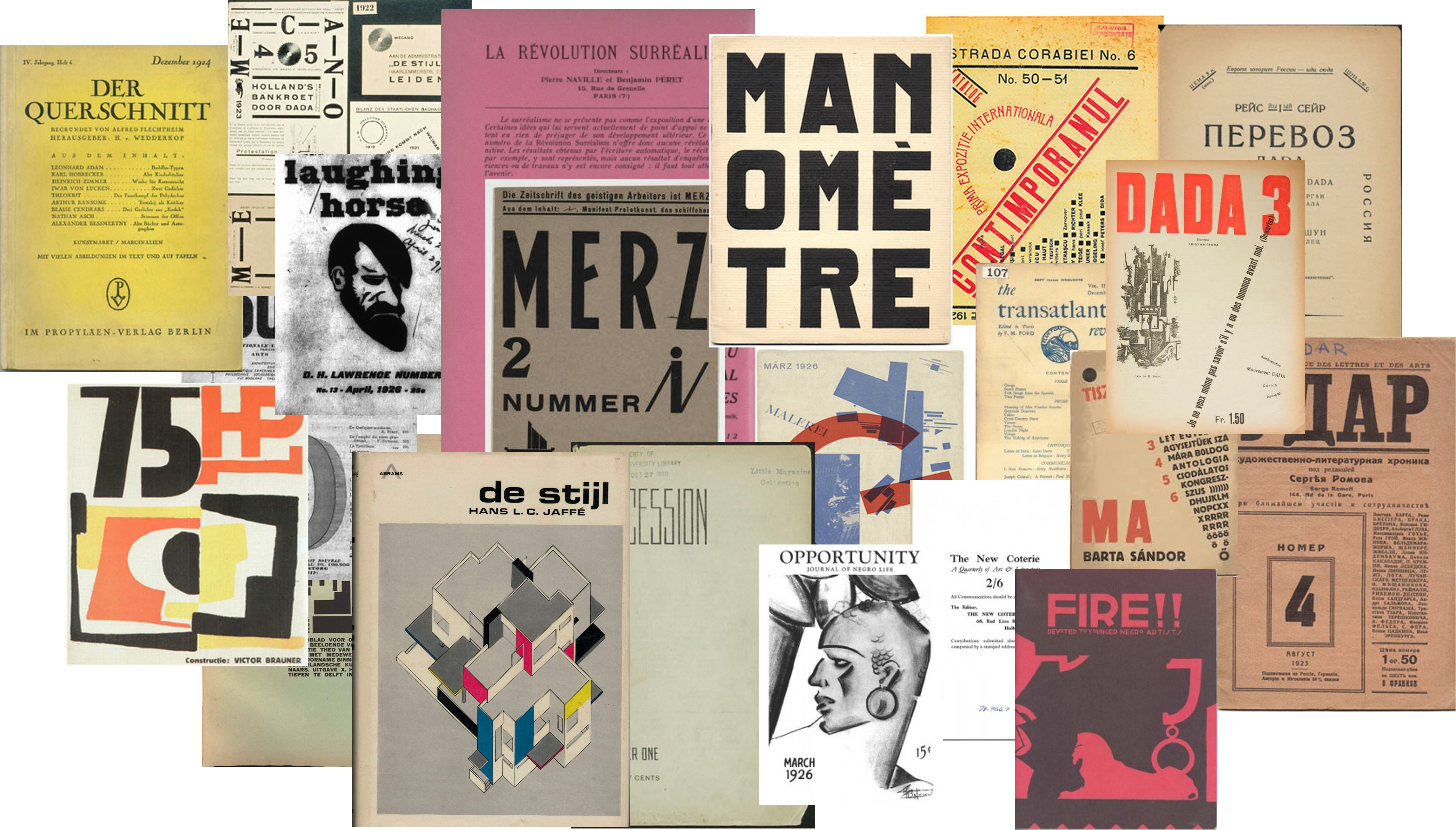

We are taking advantage of this unprecedented availability of images, on a global scale and over a long period of time, to attempt a panorama of globalisation through images based on these printed documents.

Our corpus will obviously be fragmentary, but it will always be larger and more representative than that which could have been compiled by several scholars at the end of a relentless career. This mass of documents will make it possible to ask specific questions to the series we have been able to collect. There is no need for an exhaustive numeration of past archives to reconstitute cultural circulations. Other, more recent images are also available: those of social networks. It is indeed possible to recover certain visual corpuses from certain social networks. This is an opportunity to study the circulation of digital images over recent periods - and, why not, to ask whether the logics of this circulation are so different from those of the circulation of images when print dominated.

The scientific experiment deserves several lives. We begin modestly. There are three types of digital images available to us: illustrated periodicals published throughout the 20th century having been recently digitised and made available online; works of art produced around the world over the same period, and a corpus of digital born contemporary images, circulating on diferent social networks.

In the beginning was the press.

From the end of the 19th century, illustrated periodicals - monthly, weekly, and soon daily - multiplied, particularly in the Western world. They contributed to both the nationalisation and globalisation of societies.[1]

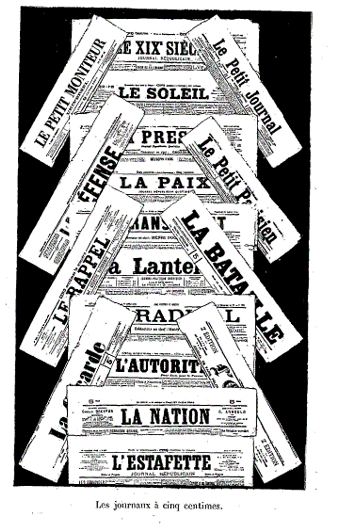

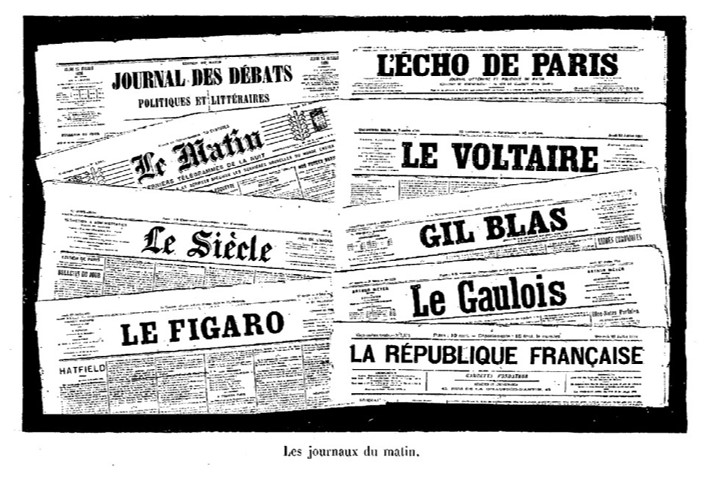

The diversity of daily newspapers from the 19th century onwards should not deceive us: it is the same layout that has been circulating for decades - and contemporaries themselves were aware of this.

In 1892, Eugène Dubief, editor-in-chief of the Journal de Versailles, in his book Le journalisme published by Hachette in 1892, used images to show this homogeneity in diversity.[2] Morning newspapers, evening newspapers, five-cent newspapers, departmental newspapers - in diversity, a visual unity spread from one town to another, from one social milieu to another.

"Les journaux à cinq centimes" (Overhead: "les journaux des départements"). In Eugène Dubief, Le journalisme (Paris: Hachette, Bibliothèque des merveilles, 1892, p.246/p.262). Source : Gallica ark:/12148/bpt6k203212x

"Les journaux du matin". In Eugène Dubief, Le journalisme (Paris: Hachette, Bibliothèque des merveilles, 1892, p. 247). Source: Gallica ark:/12148/bpt6k203212x

In the illustrated press, images of all types circulated: portraits, advertisements, news illustrations, works of art; and for all audiences - adults, women, men, workers, collectors, children...

The immediate research value of these sources is that each image reproduced in a periodical can be associated with a precise date and place of publication. We therefore have the indicators of a minimal circulation, from which a certain historical cartography of visual globalisation can be reconstructed.

For some periodicals, we know with certainty that they circulated throughout the world.

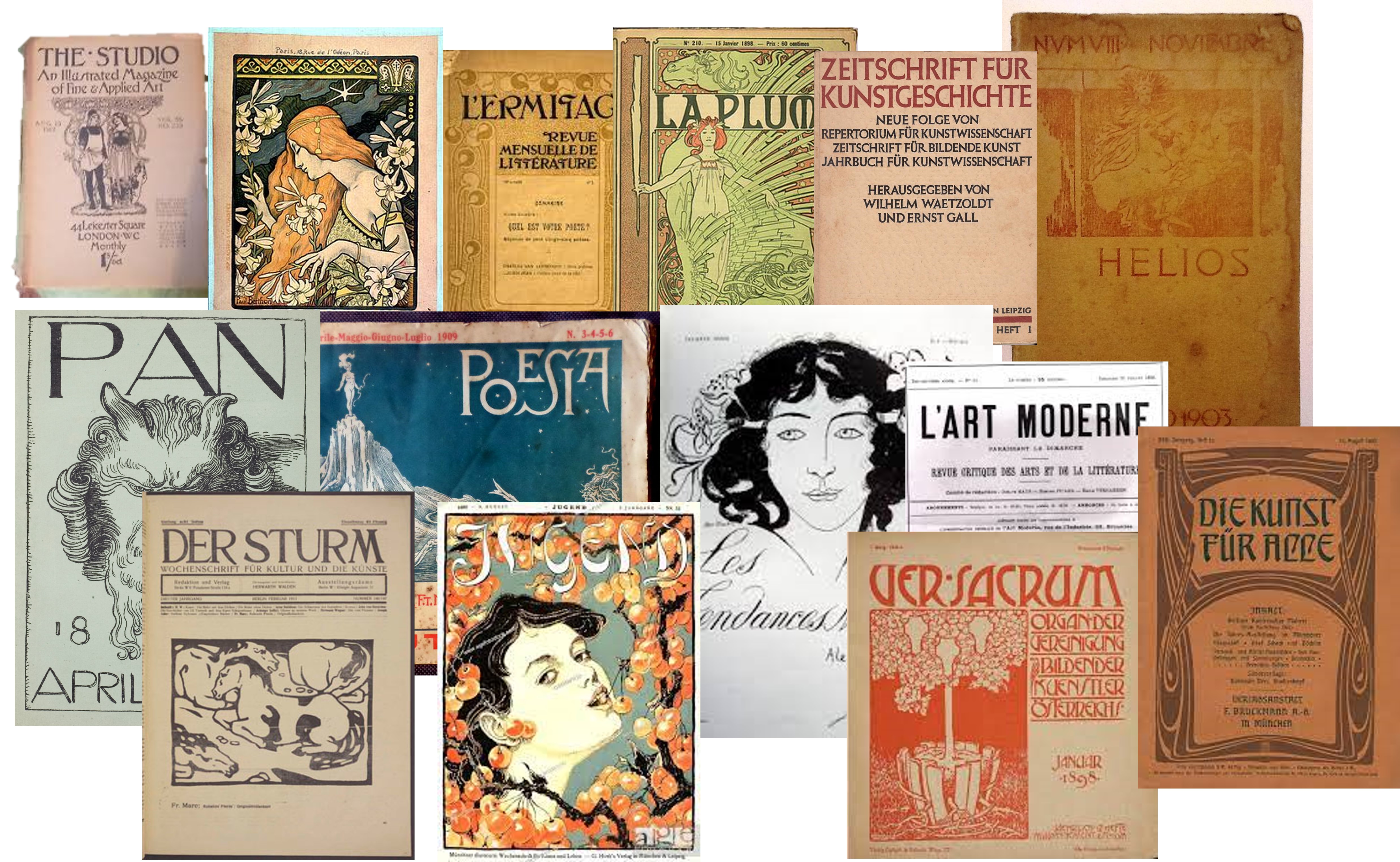

This is the case for small sized illustrated journals.

The British magazine The Studio, founded in 1893, published monthly illustrated articles on the applied and fine arts of its time. It circulated in studios, salons, and circles of art lovers and collectors. The Studio became an inspiration for other art and decorative art magazines founded in the same decade - Jugend (Munich, 1896), Volné Směry (Prague, 1896), Art et Décoration (Paris, 1897), Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration (Stuttgart/Darmstadt, 1897) and Dekorative Kunst (Munich, 1899). The Studio began to publish foreign editions, from 1897 in the United States, then in France from 1898 onwards; while L'art décoratif (Paris, 1900) was a French version of the German journal Dekorative Kunst. The images whose circulation we are tracking spread far beyond their initial place of publication.

The long and varied international span of Life

The model of an international press, still intended for a cosmopolitan elite before the 1940s, was systematised after the Second World War with illustrated magazines, and aimed at much wider audiences.

Based on the model of Life (1936), the magazines ¡Hola! (Madrid, 1944) and Paris Match (Paris, 1949) marked a globalised circulation of illustrated information. Time and Newsweek inspired the creation of Der Spiegel in Germany (1946) and L'Express (1953) in France, while Eiga Geijutsu in Japan (Tokyo 1946) was called the Japan Times, but published mainly on cinema. Some magazines, such as Life and Time, reach beyond the linguistic areas of their countries of origin. Like them, ¡Hola! was soon published in local editions in a dozen Spanish-speaking countries (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Mexico, Peru, the Philippines, Puerto Rico and Venezuela), but also in Canada, Greece, Thailand, the United Kingdom and the United States.

The circulation of models and layouts sometimes means that the same faces circulated from one cover to the next - world-famous Hollywood film stars such as Marilyn Monroe and Grace Kelly, beloved princesses such as Lady Diana and Charlotte of Monaco, leaders of the world's great countries such as Kennedy, Khrushchev and General de Gaulle.

It is also often the same layout and the same lighting that circulates: red and black frame, magazine title at the top of the cover - the indications are clear, this is a magazine that like Time will publish illustrated articles on the political and cultural current events of the West. The use of white faces with unslanted eyes on the covers of Chinese illustrated magazines confirms this Western agenda.

The general context of illustrated prints of the past is not unknown to historians.

We will not be satisfied with a study of images that have magically circulated. Indeed, we often know the cultural and social profile of their readers, their financial logic, and sometimes their scores and geographies of distribution. The great diversity of available periodicals thus makes it possible to evaluate how certain images have circulated more than others according to social circles, languages and cultures, but also according to technical possibilities, editorial networks or the geopolitics of a given period. It allows us to consider possible contagions between advertising and art, art and advertising; between news and cinema images, art and documentary images. We can assess whether certain images have circulated in certain regions and circles rather than others - tracing, however crudely, the visual contours of certain ethnoscapes, highlighting perhaps the diffusion or otherwise of certain practices associated with these images; or at least the diffusion of incentives for certain consumption practices, in the case of advertising.

Other digitized sources to track the global circulation of images: artworks and social network images.

Read more art images and social networks.

[1] Arjun Appadurai, Après le colonialisme. Les conséquences culturelles de la mondialisation (Paris: Payot Rivages, 2015, p.28-29) -translated from: Modernity at Large. On the unprecedented development of illustrated periodicals in the late nineteenth century, see Evanghelia Stead & Hélène Védrine (eds.), L'Europe des revues (1880-1920): Estampes, Photographies, Illustrations (Paris: PUPS, 2008); Stead & Védrine, L'Europe des revues II (1860-1930), Réseaux et circulation des modèles (Paris: PUPS, 2018). On the explosion of the press during this period, see for the French case Christophe Charle's synthesis, Le siècle de la presse (1830-1939) (Paris: Seuil, 2004); as well as Dominique Kalifa, Philippe Régnier, Marie-Eve Thérenty and Alain Vaillant (ed.), La Civilisation du journal. Histoire culturelle et littéraire de la presse française au XIXe siècle (Paris: Nouveau Monde Éditions, 2011).

[2] Eugène Dubief, Le journalisme (Paris: Hachette, Bibliothèque des merveilles, 1892).