Other digitalized sources to study globalisation through images?

Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel & Nicola Carboni

Art is, as much as the press, an extraordinary prism for tracking globalization through images.

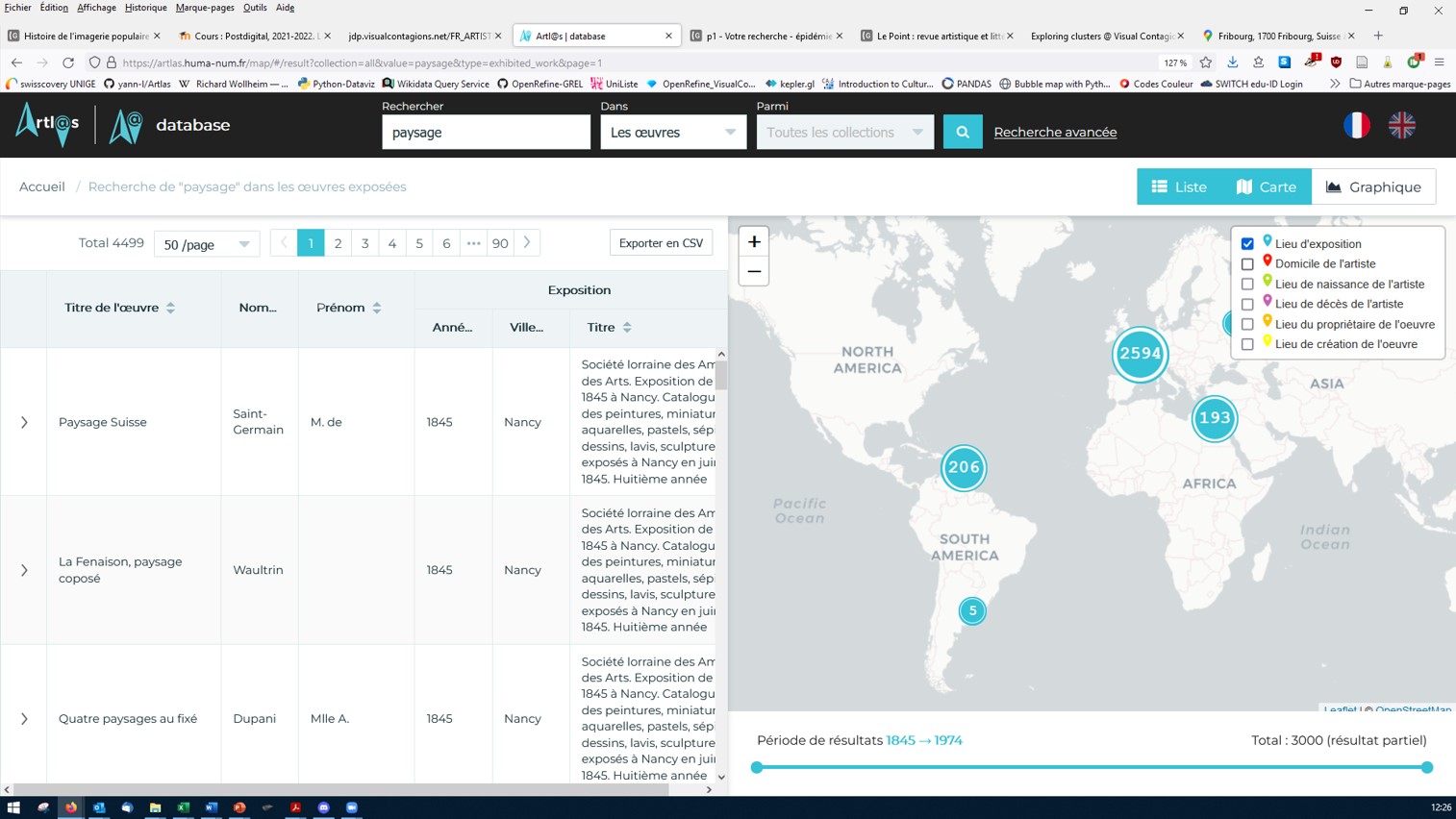

Exhibition catalogues are a privileged source for this work. Each catalogue gives a list, abundant in number, of works of art exhibited in a given place and time. Each work is often associated with its title, the name of its presumed author, information on its medium, sometimes its date, its price and its owner. From one catalogue to thousands, what a boon for studying artistic globalisation!

Visual contagions is a continuation of an older project, Artl@s.

This project starts from exhibition catalogues to track, on an international scale and over the long term, the worldwide circulation of artworks, styles and artists. A single exhibition catalogue makes it possible to find out where a work of art or an artist has exhibited on what date. When we go from one catalogue to thousands, it the analysis becomes possible on a global scale and on extended populations.

--

What does an exhibition catalogue contain? In addition to information on the works exhibited, where and when they were exhibited, and by which artists, an exhibition catalogue often gives access to information on the artist's residence, the place where the work is kept, and sometimes even the exhibitor's place or country of birth. This is exceptional information for reconstructing the worldwide circulation of artistic careers and the international art market.

--

Artl@s makes available to all a worldwide collaborative database of exhibition catalogues, accessible through a spatio-temporal platform.

Art also circulates in the press.

There are many reproductions of works of art in art magazines published since the end of the 19th century, reproductions that can sometimes be linked to their "originals". Knowing the date and place of the original image, as well as that of each reproduction, we can reconstruct distributions.

If we want to collect these "originals" of works of art, only art before the 1950s is really available, because of copyright rules. We take advantage of the images made available by Wikipedia and by some museums.

It is then possible to sketch out the commercial routes of cultural goods, the circulation of artists, the diffusion of styles and tastes. The global circulation of works of art is still an excellent starting point for studying the world geopolitics of art, too often presented as the history of the successive dominations of Paris until 1945 and of New York since then. How do certain practices and aesthetics appear or disappear? How do certain themes, which were not even conceivable at certain times (technically, morally or culturally) end up spreading and becoming obvious? When did Impressionist painting enter the mainstream press? When did Fauvism finally make it into the international elite's magazines? When did New York dripping appear in advertisements or on clothes? When did pop art, itself taken over from the comic strip genre, become a new media aesthetic? ... So many questions to ask from our corpus 1 (illustrated periodicals) to our corpus 2 (artistic images).

Social networks and globalization through images

Last, but not least, the Visual Contagions project focuses on bodies of contemporary images - those circulating on social networks.

With the growing share of technology in our daily lives over the last twenty years -smartphones and computers, for example-[1], it is impossible not to consider social networks as sources for our contemporary visual culture(s).

Instagram, Facebook, TikTok, 4chan, Snapchat, Pinterest, among others, are platforms where everyday the number of images produced exceeds all those we will see in our lives.[2]These social networks are not disconnected from other visual regimes - illustrated magazines, film or political posters, television series and streams. They are a continuation of them in terms of both medium and content.[3]

There is therefore no reason why images created, disseminated and circulated before social networks stopped circulating in 2004 (when Facebook was created) or even in 2010 (when Instagram was founded).

Why wouldn't they also circulate in Twitter, Facebook and Instagram? By linking our corpora 1 and 2 (print periodicals and art images) to our corpus 3 (social network images), we give ourselves the possibility to consider a continuity of content between images from different times, places and media.

Read more:

In the Project's kitchen

Go back:

An epochal possibility: the digitized past

Chapter:

II. Promises of the machine

[1] The annual studies of the WeAreSocial website report on contemporary digital dynamics and disparities.

[2] To see for yourself: https://www.internetlivestats.com

[3] ] Dieter Mersch, Media Theory - An Introduction, 2018, p. 125; Arjun Appadurai, After Colonialism: the cultural consequences of globalization, Paris, Payot Rivages, 2015, p. 98.