Do we share our jokes between countries? Humor in pictures, on a global scale.

Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel & Nicola Carboni

"The engraving is of all languages..."

When, in February 1864, the Journal illustré, a weekly newspaper appearing on Sundays, associated with the Petit Journal press group and sold for 10 cents, Timothée Trimm, a renowned editorialist of the Petit Journal, presented the program:

"you will have (...) the view of the whole world, all the buildings, all the vegetation, all the costumes of the peoples of the earth (...) the whole panorama of the universe". The whole, according to a certainty asserted drumming: "The engraving is of all the languages (...). It represents, in flesh and bone, from foot to cap, the heroes of the narration (...). It is sovereign, absorbing, imperious; and the text, whatever it is, must be only its very humble subordinate"[1].

The Illustrated Newspaper was itself based on the model of the Penny Illustrated Paper, which had appeared in Great Britain since 1861. Designed to compete with L'illustration, a magazine that sold for 75 cents, it was sold for 10 cents each Sunday, making it accessible to the middle classes.

Given the success of the enterprise, twenty years later the director of Le Petit Journal launched the weekly Supplément illustré, where color illustrations made the difference in a growing market for illustrated papers. In 1890, the illustrated supplement of the Petit Journal replaced the Journal illustré.

If the idea that the image imposes itself whatever the language is old - and also very present in the art criticism of the time, at the time of the International Exhibitions [2] -, it does not necessarily materialize in all the fields. Notably for the press image, and more precisely for the satirical image.

-

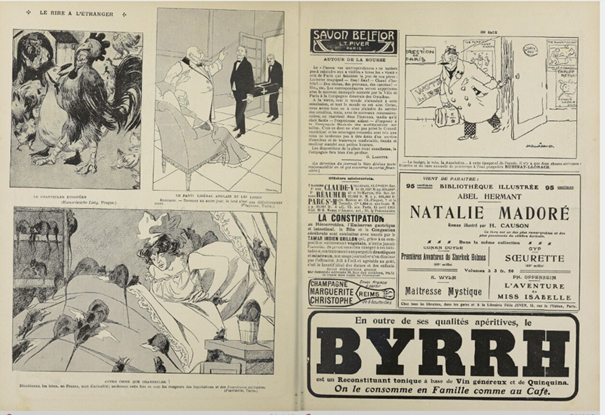

At the beginning of the twentieth century, satirical magazines all had their pages on "foreign humor", and this tradition has not disappeared today.

Between the French magazine Le Rire, its German equivalents Fliegende Blätter, Lustige Blätter, certain pages of Jugend, or the English magazines Punch, Papitu in Barcelona, Pasquino in Milan, La lente in Florence, or the American magazines Puck and Judge, one sees a network of references being constituted where the image plays a central role, legible, comprehensible, vector of effective information on the current events of other countries.

In these sections on the foreign satirical press, everyone draws from the others somewhat distant points of view on current events, whether it be information on the country concerned or international news.

Does this mean that cartoons are really circulating on a global scale?

It is actually quite rare that these columns share the same cartoons.

The source, the country and the context of the scenes taken from the others are made explicit in a more or less clear way -- sometimes not at all, as illustrated by this page of Papitu published in Barcelona on July 3, 1912; sometimes much more explicitly, with this sequence of cartoons borrowed from the Turkish satirical weekly Pasquino. The captions of the original cartoons are in any case maintained and translated most often. On the other hand, one sometimes suspects that some magazines compose their foreign section from the foreign section of other more accessible magazines. The chronologies of publication of some cartoons are shifted (below), and the quality of the drawing is progressively less good.

--

Le Rire, Nouvelle Série, Paris, N° 373 – 26 mars 1910. p. 11.

--

"Come back another day, the lord is not definitely dead."

The king calls out to two men in civilian clothes ready to carry the widower's body away in a coffin -- the first, on the left, represents the liberal Chancellor of the Exchequer, David Lloyd George, who since 1909 had been trying to get a tax on large fortunes passed, despite Tory opposition.

--

Jugend, n° 16, p. 377, Paris, 1910.

--

This cartoon depicts King Edward VII watching over an elderly Lord slumped in an armchair at the end of his life.

--

Papitu, Barcelone, année III, N° 71, 6 avril 1910, p. 222.

--

In the spring of 1910, British institutions were in crisis, following the veto in November 1909 of the very conservative House of Lords against the draft People's Budget. In January 1910, the King called an early election, which did not produce a House of Commons united enough to resolve the situation. The crisis would drag on until 1911.

It is likely that, taking advantage of the recent techniques of photographic transfer of press illustrations,[3], some cartoons were themselves the result of reproductions of originals from the foreign press.

--

Technical reproduction challenge: On the right, an image from the Jugend magazine (Munich, Germany, 1899), on the right the same image found in Le rire : journal humoristique (Paris, France 1901). By clicking on each image, you can access its original page. The illustration was borrowed from Life magazine. The difference in quality between the two images is particularly revealing of the technical challenges of reproduction...

Satirical magazines in general share few clusters of similar images. Images in the humorous press do not cross borders very well -- or for them to cross borders, they obviously have to deal with crises serious enough to attract the interest of foreign countries.

--

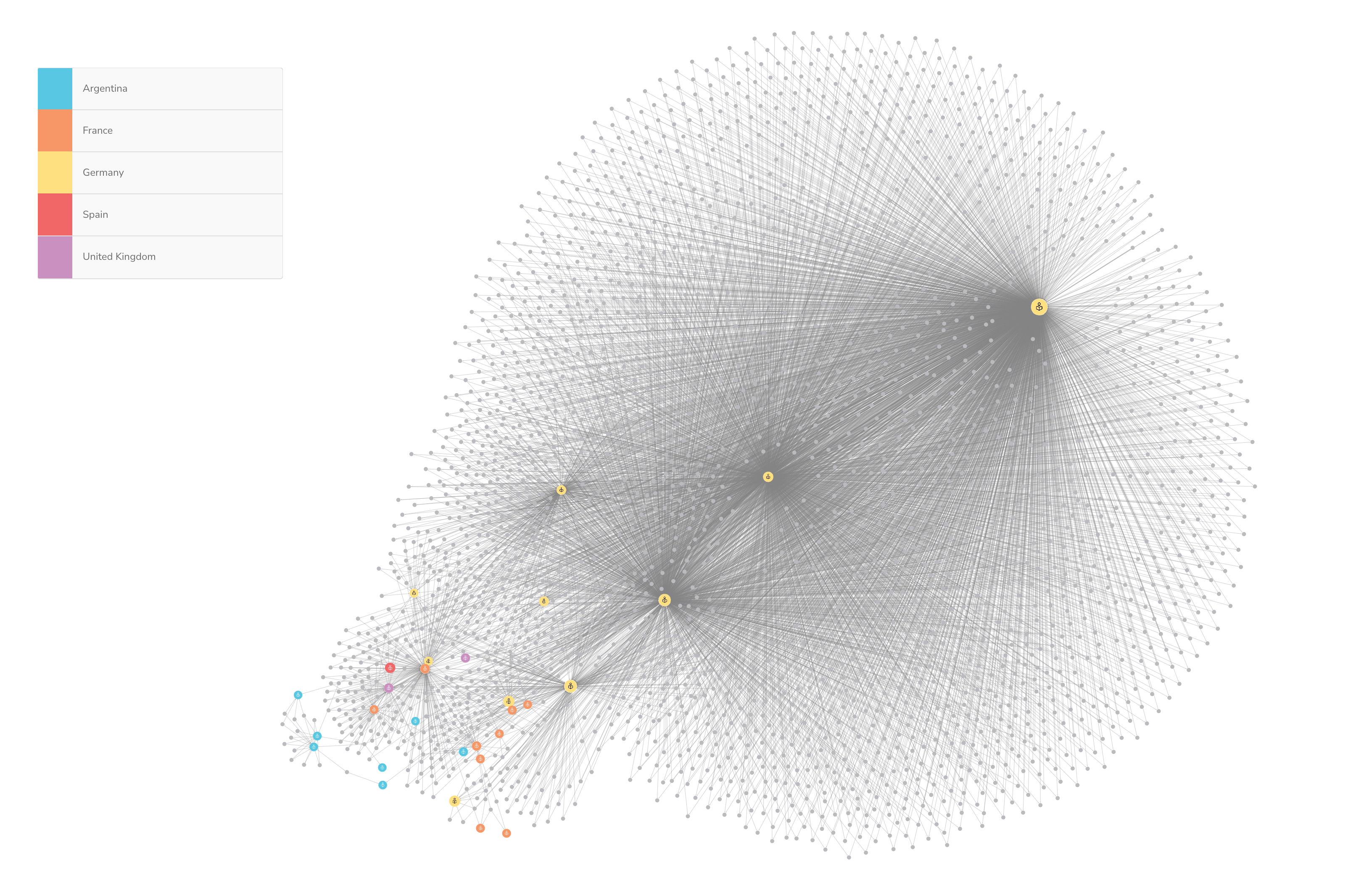

In illustration, the network of image clusters shared by the humor magazines in our corpus. The colors of the nodes represent the country where the magazine was published. Blue represents Argentina, orange France, yellow Germany, red Spain and purple the United Kingdom.

The network easily reveals the strong interconnection between German journals (yellow), but also the international character of some representations (interconnection between France, Argentina and Spain).

What the periodicals share, however, is a style; that of satirical drawing.

Our algorithms, when asked to search for images close to a given cartoon, bring back satirical drawings in black and white, taken from all over the place, without a particular theme bringing them together. They are very generic visual elements that bring them together: the black line of the press drawing, one or two surfaces completely colored black, a gray background, a multiplicity of characters.

All these images are in any case satirical drawings. The machine is not mistaken.

When the cartoons are in black and white, the algorithm gathers a worldwide corpus. When the illustrations are in color, it gathers much more national groups.

The French illustrated prints form a particularly coherent group - according to the very characteristic colors of the illustrated supplements of the late 19th century.

Is this grouping a national style? Not necessarily. Rather, this body of images with similar colors seems to come from the same printing house, the one that at the end of the 19th century supplied some sixty provincial newspapers with the same illustrated supplement.[4].

--

The front pages of several weekly illustrated supplements, headlined on April 22, 1900 on the inauguration of the 1900 World's Fair. The algorithm gathered the following titles: Le Petit Dauphinois illustré (Grenoble, April 22), Le Petit Méridional (Montpellier, April 22), Le Télégramme d'Indre-et-Loire (Tours, April 22), L'Avenir du Cantal (Aurillac, April 22), La Semaine illustrée (Paris, April 22), le Supplément illustré du Moniteur des Côtes-du-Nord (Saint-Brieuc, April 22), le Journal de Dreux (Dreux), and L'Impartial de l'Est (Nancy). Only L'Indépendant de Saint-Claude (Saint-Claude) seems to be published later than the other press organs (April 28). The last image, at the bottom right, is not identical to the others (its similarity score, 0.43, is much lower than the previous images, which are similar to each other).

--

Overhead: various illustrated supplements, series "Anecdotal History of the European War", circa 1915 (undated - #46, for each version).

The satirical magazines of our corpus also share, at the beginning of the 20th century, a tendency to diffuse and illustrate received ideas.

Their illustrations often support nationalism, racism and anti-Semitism. If our algorithms are insufficient to gather groups of images that could each be put under such a label, the visual stereotypes are nevertheless numerous - bankers with aquiline or over-extended noses, obese bourgeois, fat wives with stupid smiles, half-naked Africans[5].

When one mocks, one belittles the other.

Each in his own way, even without sharing specific motifs and images from one country to another.

We don't share our jokes much, well, internationally, because humor is never just about image. It is also a question of language, of words, of culture(s).

Images are understood in a context of language and culture that we tend to forget. Proof if it were needed, the caricatures of the first 20th century are always accompanied by texts which explain them.

In the era of the explosion of illustrations in the press, posters, books, it is a question that the philosopher Henri Bergson tackles, without formulating it clearly, in 1900 in the Revue de Paris.[6] : seeking to illustrate how much comedy is the effect of automatism - notably that of the civil servant applying rules automatically out of context, he immediately turns to an example taken from the press:

"I pick out of a newspaper, quite at random, an example of this kind of comedy.".

And a few lines after describing the scene, Bergson quotes the caption:

"About ten years ago, a large liner was wrecked in the vicinity of Dieppe. A few passengers were struggling to escape in a boat. Customs officers, who had bravely come to their rescue, began by asking them "if they had nothing to declare". (here).

We remembered from Bergson's Laughter that he defined comedy above all by stiffness (rather than ugliness), the automatic and robotic gesture cutting with the normal and usual attitude of a body, of a gesture, of a reply. But Bergson posited, before this quasi-visual approach to comedy, an essential remark:

"One would not enjoy laughter if one felt isolated. It seems that laughter needs an echo."

--

Henri Bergson, "Le Rire", La Revue de Paris, janvier-février 1900, p. 514.

Laughter is a story of community.

"The comical is unconscious." It is "a kind of social gesture[6]".

Does this mean that a machine will never be able to locate on visual corpus the images likely to make people laugh? The comic is a mechanical effect, an automatism; but it is quite clear that neither mechanics nor automatism will allow to trace it visually.

Read More :

This summer, getter bigger breasts and grow your hair back......

Go back :

Come Play Along !

Chapter :

V. The Machine's Hoaxes

Notes :

[1] Jean-François Tétu, « L’illustration de la presse au xixe siècle », Semen [Online], 25 | 2008, URL : http://journals.openedition.org/semen/8227 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/semen.8227.

[2] Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel, "Nul n'est prophète en son pays"? L'internationalisation de la peinture des avant-gardes parisiennes, 1855-1914, Paris, Musée d'Orsay/Nicolas Chaudun, 2009, chapitre 1, "La grâce divine du cosmopolitisme", p. 15-25.

[3] Thierry Gervais, L’illustration photographique. Naissance du spectacle de l’information (1843-1914), Thèse de Doctorat en Histoire, Paris, École des hautes études en sciences sociales, 2007.

[4] Quelle imprimerie pouvait fournir un marché national aussi large ? Difficile de le déterminer, même en croisant les sources et les périodiques. Les pages de couverture mentionnent toujours l'"Administration" du supplément illustré, une adresse d'abonnement et un point de contact pour les annoncer; jamais l'imprimerie. On sait en tout cas, grâce au travail des bibliothécaires et des archivistes qui ont classé et numérisé les imprimés en question, que la plupart des suppléments illustrés étaient imprimés à Paris. Le Supplément illustré du Petit Méridional paraissant à Montpellier, par exemple, était imprimé dès les années 1880 par l'Imprimerie Tolmer et cie.

[5] Voir par exemple Alaistair B. Duncan et Anne Chamayou (dir.), Le rire européen, Perpignan, Presses universitaires de Perpignan, 2010, http://books.openedition.org/pupvd/3177. DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/books.pupvd.3177.

[6] Henri Bergson, "Le Rire", La Revue de Paris, janvier-février 1900, p. 520 et 521. Les articles de Bergson sur le Rire furent réunis en un livre, Le Rire, publié la même année chez Félix Alcan (consultable sur Gallica).