Explain.

How do images spread ?

Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel & Nicola Carboni

Characterize, describe -these first two steps in the study of an epidemic are the prerequisites for an even more important approach: that of explanation. How did a contagion spread? We ask ourselves similar questions for the circulation of images, except that we do not need to stop these epidemics. If one image circulates more than others, is it because of factors that we could isolate?

The possible factors of circulation, for an image, can be very diverse.

Some work in cognitive science suggests that the images that have been most successful may follow specific visual and formal criteria.

We know, for example, that the human brain easily recognizes familiar figures in a priori abstract forms - faces, animals, that is to say forms that it would be necessary to know how to recognize in order to survive (to recognize affectionate faces, to flee from dangerous people and animals, etc.)[1].It is from these reflexes that our capacity for pareidolia is born, i.e. to recognize specific forms in visual stimuli without clear characteristics. Are the images that circulate the most successful because they correspond to our cognitive propensities? Brighter colors, rounder faces, more familiar scenes... In line with the works of anthropologist Dan Sperber, for whom the ideas that circulate best are simply the simplest ideas[2], some researchers have even tried to show that the images that "work" best are simple images. But would we really say that the most present and most international images in our corpus are so simple? And what does a "simple" image mean? It may be true for the diffusion of portraits (more frontal and smiling to make them work better); or for busts (which represent human figures, so they may have circulated better for this reason). But would a photograph of an automobile - one of the most widespread images in our corpus - be simple?

Formal criteria alone do not explain the success of an image.

The case of avant-garde works (at the time of their creation) is very revealing of the gap between the formal criteria of an image, and its success of esteem.

The works of avant-garde which circulate with more than a handful of specimens, in our corpus, were generally reproduced years after their conception, whereas they had already circulated much in exposures.

Some of Paul Cézanne's paintings, such as Partie de cartes , only appear in our corpus after a generation - after 1914 and especially in the 1920s for the version now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. In this case, the "success" of the Cézanne can certainly not be linked to objective formal criteria of image composition. It took a few years for Cézanne's paintings to be appreciated. There is no way to attribute to the painting an objective value, a timeless or unquestionable beauty. The success of the pictures in the illustrated press clearly has to do with the reputation of the pictures and the artists who created them - at least for art.

--

Paul Cézanne (1839–1906), La Partie de cartes, 65,4 x 81,9 cm, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

This painting does not appear in our corpus of illustrated periodicals before 1914, or even before the 1920s.

The Cézanne is not an isolated case. Georges Seurat's Le Cirque de Georges Seurat (Musée d'Orsay, Paris), a canvas painted in 1891, does not appear in our periodicals until 1912, and again for the exception of a Prague magazine, Umělecký mĕsíčník, and then only in 1918 (Vell i nou, Barcelona) and in the 1920s[3].

How many years does it take on average for an artistic image to be reproduced, after its conception date? We are working on this question for works of art, depending on whether they were of classical style, or considered avant-garde at the time of their creation.

Thus, we must look for the factors of virality of an image not on the side of its visual and formal characteristics, but on the side of a possible adequacy between the image and the expectations of a precise public in a given place and time.

If we limit ourselves to the iconographic (what the image represents) and iconological (the meaning of what it represents) characteristics of an image in order to explain its success and circulation, we run the risk of never arriving at a general explanation of the virality of images. Besides the fact that we do not believe that a single formula can account for the circulation of any viral image, it is obvious that the success of an image can also be linked to factors external to it - to ideas, practices, social positions, desires and expectations that can justify a non-formalist, but more socio-historical and critical epidemiology of images.

The diffusion of certain images is less a question of form and taste than of social behaviors of distinction. This is particularly true of photographs of busts.

Epidemiology is interested in the behavior of crowds, and the effects of this behavior on the diffusion or not of the contagious phenomenon.

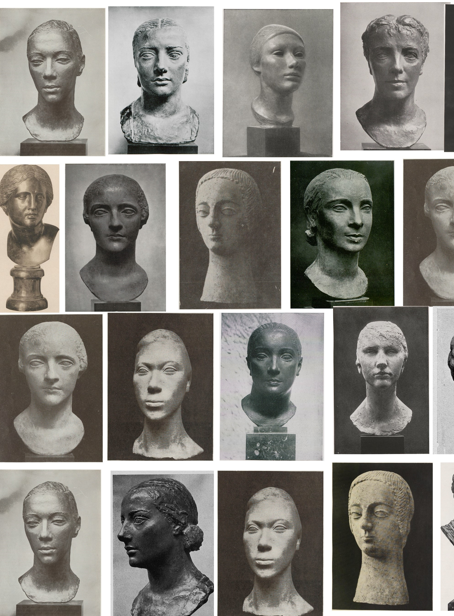

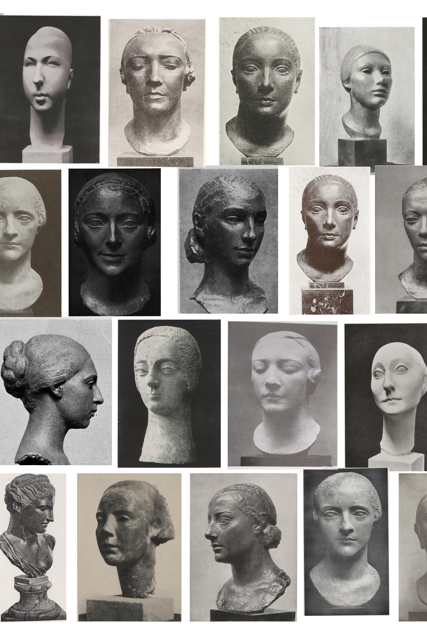

How can we better explain our bust diffusions? The shape of the bust frequency curves in our illustrated periodicals as well as that of the bust frequency curve in the exhibition catalogs of the Artl@s database, indicates a diffusion of busts similar to a punctual epidemic process. For the 1920s and 1940s, the curves are similar to phenomena in which the "cases" were "infected" during a rather brief event. Following the event, the number of infected cases increases sharply, reaching a maximum followed by a gradual decrease.

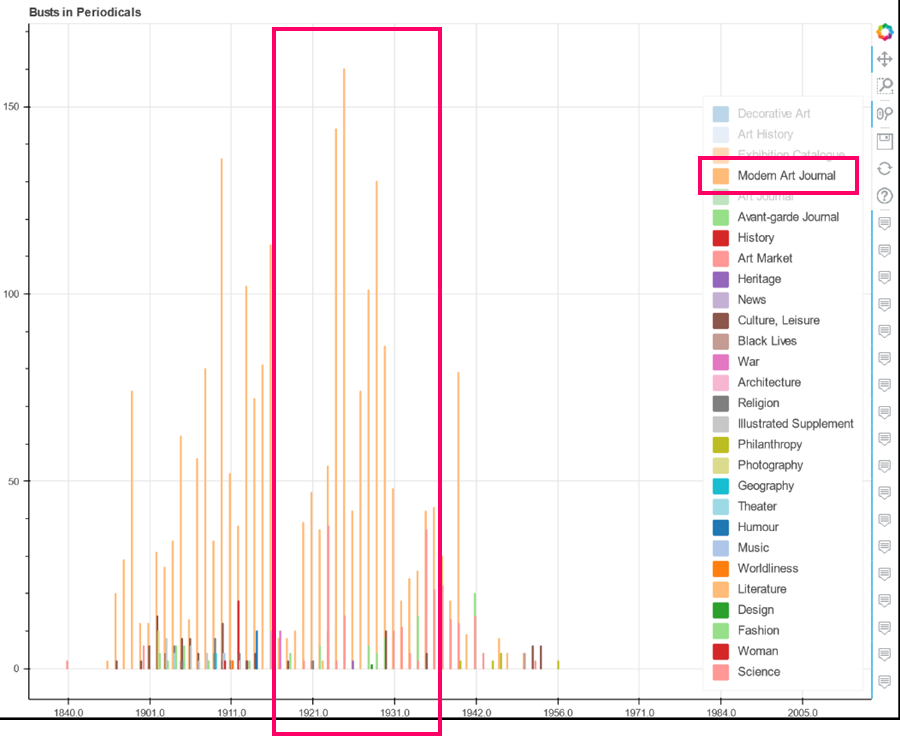

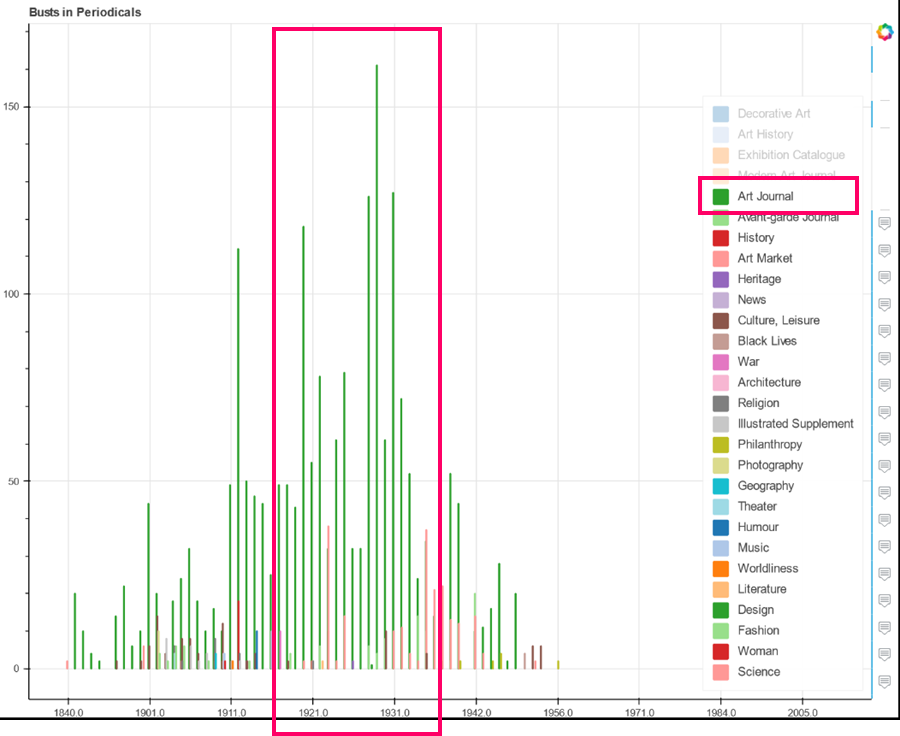

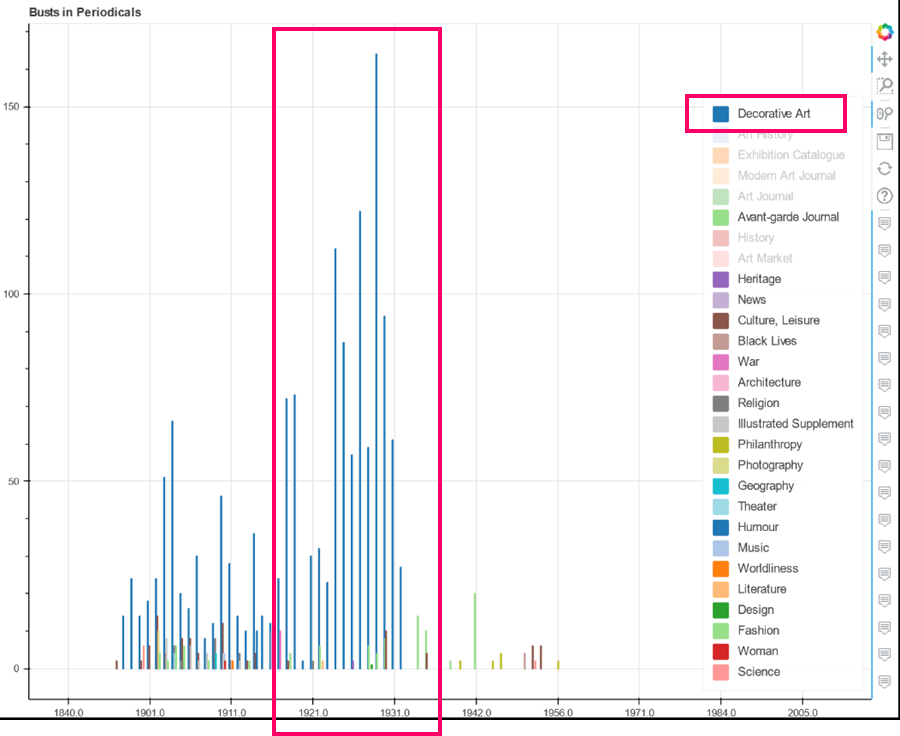

The question is then to isolate the event that may have triggered the epidemic. Where, first of all, could the event have taken place? If we analyze our images according to the type of magazine that published them, we find that the reproduction of photographs of busts is done almost exclusively by art magazines (art history, modern art, decorative arts... - see the graphs below: Fig.1 to 3). The fashion of the busts is thus to be sought on the side of the field of the art, and the events which animate it - exhibitions, Salons and sales for the essential one. But what kind of events, and what kind of circles are associated with them? Is it a modern fashion, or a conservative fashion?

--

Fig. 1. frequency of reproductions of busts in the modern art magazines of the Visual Contagions corpus.

--

--

Fig. 3. frequency of reproductions of busts in the normal art magazines of the Visual Contagions corpus.

--

--

Fig. 2. Frequency of reproductions of busts in decorative art journals in the Visual Contagions corpus.

--

For the 1920s, the fashion for busts seems to have been earliest in modern art magazines and decorative arts magazines, before being adopted by the more generalist and less aesthetically committed art magazines. We can see, in the interactive graph below, that the art market is carrying this fashion forward in fits and starts. The art market magazines we have in the corpus illustrate more busts in 1922 and in the late 1920s. We note, moreover, that the fashion for busts in artistic circles is not reflected in cultural or leisure magazines, nor in social and fashion magazines, which seem to have been more interested in busts in the 1900s.

The phenomenon is properly artistic.

--

Interactive graph: reproductions of busts in the corpus of the project (spring 2022), according to the type of periodical that reproduces them. By right-clicking on the elements of the legend, the curve concerned disappears or appears. The highest items, in the legend, concern the most supplied curves. The lowest items concern the types of magazines in which the reproduction of busts is almost non-existent. We can thus note the over-representation of art magazines (modern art, decorative art, art history, etc.), even if avant-garde magazines are clearly less represented.

--

It is thus well on the side of the artistic events that we must look for the birth of our epidemic of busts, and probably on the side of the circles related to the modern art and the decorative art, since it is initially the magazines of modern art and decorative art which reflect this fashion in their illustrations.

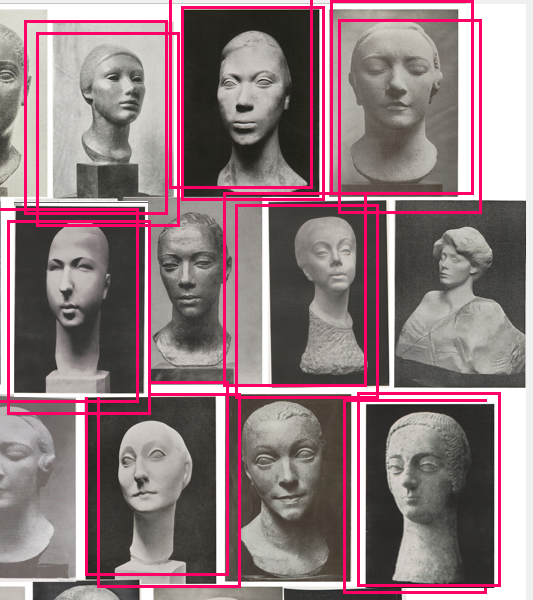

According to the Artl@s, our project's database of exhibition catalogs, the Paris Autumn Salon in 1919 suddenly saw a large number of busts appear. The trend continues for the years 1920, 1921 and 1922, before a peak in 1923 and 1924. Although the Artl@s project only has Parisian catalogs for this period, we should nevertheless emphasize the very international nature of the Salons concerned (Salon d'Automne and Salon des Tuileries). The international fashion for busts seems to be confirmed by the presence of busts in an exhibition organized in New York on Russian art in 1929 (Exhibition of Contemporary Art of Soviet Russia: painting, graphic, sculpture). But while the style of the busts of the 1900s remained classical, that of the 1920s is clearly marked by a modern, postcubist tendency to simplify forms - more angular faces, geometric nose ridges, stylization of profiles and simplification of hairstyles.

This simplification of forms is quite typical of the good reception and classicization of Cubism.[4].

Some busts were clearly inspired by the primitive arts, which were particularly popular on the art market at the time - not only did auctions favor African and Oceanic art, peaking around 1925, but some exhibitions at that time featured African busts[5]. In 1935, the "African Negro Art" exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art presented four busts lent by the Parisian galleries Paul Guillaume, Charles Raton and Louis Carré, as well as by the Museum für Völkerkunde in Berlin. A fine consecration for this type of work of art.

The fashion for busts in the 1920s seems to be linked to the consecration of modern art in the elite collectors, now interested in the realization of their own bust in the cubist manner.

A manner itself largely inspired by the primitive arts, which were highly prized on the art market at the time.

Desiring machines

It is quite possible that most of the viral images we are studying are linked to comparable phenomena of fashion and social distinction. This is certainly the case for photographs of automobiles, which are not all the result of advertising practices alone, since they are also reproduced to illustrate articles of current events or contemporary culture.

The representations of automobiles were first conveyed by the press, not only as purely aesthetic objects, but also as symbolic objects that embodied (and still embody) the possible access to a higher social status. The car has never been a purely functional object; on the contrary, its image has always aimed to evoke prestige, power, domination, potential envy and jealousy of others. For it is indeed from images that desire is nourished.

Tracking down the images in circulation is thus to be able to follow how and where certain collective desires have been propagated. By analyzing each link of a chain of desire, by reconstituting how each chain is itself part of a much larger libidinal mechanism, it is a contagious machine guided in its heart by imitation and desire that comes to light. A machine that has propelled and still propels given images, values, practices and representations throughout the world, among nations, social strata, cultural strata, or generations.

Notes

[1] J.L. Voss, K.D. Federmeier & K.A. Paller, "The potato chip really does look like Elvis! Neural hallmarks of conceptual processing associated with finding novel shapes subjectively meaningful", Cereb Cortex, octobre 2012, (10): p. 2354-2364. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr315.

[2] Dan Sperber, La Contagion des idées, Paris, Odile Jacob, 1996.

[3] See the reproductions of Seurat's Circus recovered by the Explore platform: : https://visualcontagions.unige.ch/explore/duplicates/clusters/00000c001a3e89f11c57cde8adac3e84dbc984c4ecf0a03b780f10767b90c3f2257d6bde

[4] On the consecration of cubism in the 1920s, see B. Joyeux-Prunel, Les avant-gardes artistiques. Une histoire transnationale, vol.2 (1918-1945), Paris, Gallimard Folio Histoire, 2017.

[5]In particular l'Exposition d'art africain et d'art océanien organized in Paris in 1930 by the Pigalle Gallery, which presented a dozen busts. On the success of primitive arts in Parisian auctions in the 1920s, see Léa Saint-Raymond, A la conquète du marché de l'art. Le Pari(s) des enchères (1830-1939), Paris, Classiques Garnier, 2021.

Read More :

1. Characterize. Is a circulation of images necessarily epidemic?

2. Describe. Where, when and how fast? How?

3. Explain. Are there laws of imitation for images?

4. Experiment.

Chapter