When Dracula was preying on ... cinema

Adrien Jeanrenaud

The few appearances of vampires that we can find in the 20th century press associate the vampire, in the guise of a bat, with the phenomenon of anxiety. Image or incarnation of nervous, sexual or geopolitical anxiety, the bat seems to "vampire" everything. The images of our corpus often show it coming out of the shadows, where it was lurking, to expose our fears.

Throughout the 20th century, these vampires that expose our anxieties are present in visual culture, in the press and illustrated newspapers; they are even more present in the cinema. The most famous of them - Dracula - came out of literature at the beginning of the 20th century to flood our dark rooms.

--

Modern Publicity Illustrated Magazine, January 1, 1972, London. Available on the Mirador of the University of Geneva

The strange atmosphere of Dracula

The images of Dracula are first of all an atmosphere. The illustrators were, of course, inspired by the novel of the same name. But nothing is quite clear in this novel to be put into images. From the very first lines of Dracula, Bram Stoker confuses the reader. On the train to Budapest, narrator Jonathan Harker, on his way to Castle Dracula, shares his impressions:

"The impression I had was that we were leaving the West and entering the East; the most Western of splendid bridges over the Danube, which is here of noble width and depth, took us among the traditions of Turkish rule[1] ».

Leaving modern Europe for the ancient East. Leaving the light of the cities for the darkness of unknown places. Dracula is a journey through cultures and their imaginations[2]. Jonathan Harker, like the audience of Dracula during the 20th century, feels this constant movement from one place to another, between light and shadow.

--

Production of Dracula films in world cinema (1895-2022). Source: The Movie Database (TMDb). Map: Adrien Jeanrenaud.

Since the first edition of Bram Stoker's novel in 1897, the book has not ceased to be read, reread and adapted all over the globe. It is probably the timelessness of the story that allowed Dracula to survive and to appear, still today, in the dark rooms of our cinemas. Dracula is an eminently European subject, certainly, and very American in the world of cinema. But film versions of the novel are also produced in the East and in Asia. Obviously, Dracula is a theme that has intrigued and hypnotized across countries and continents. In short, it is a global subject - perhaps, precisely, because the shifting nature of its atmosphere allowed it to be adapted almost anywhere.

--

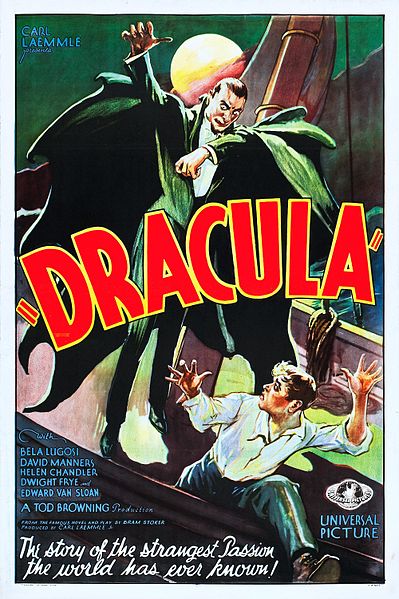

Poster for the movie Dracula, Tod Browning, Universal, 1931.

Dracula, transnational vampire

The year of publication of Bram Stoker's canonical story coincides with the birth of cinema. However, before the 1950s, the film industry's infatuation with Dracula was barely felt. A first Hungarian adaptation (Dracula halàlal, Karoly Lajthay, 1921) was made in the early 1920s. In 1922, Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau adapted it with Nosferatu. Although this film is considered today as a classic of vampire films, it obviously did not lead the way for other productions. A question of rights perhaps?

Why so few echoes in the 1920s and 1930s, and then in the 1960s-1970s cycle?

In the film industry, the popularity of a particular subject can be measured by cycles of revivals and adaptations. When a production is successful at the time of its release, it is possible that other films, of a similar form, will be produced in its wake. Here is an example of a cycle, which, according to Bordwell and Thompson[3] ».opens with a film that sets the tone for the following ones. In this sense, it is necessary to find the film that, at the beginning of the cycle, will open the way.

If we cannot reduce the craze around a production to the existence of a cycle, it is still possible to identify particular "moments" around the figure of Dracula in cinema. In the first part of the 20th century, neither Murnau's Nosferatu (1922) nor Tod Browning's Dracula a decade later immediately opened a cycle. So how can we explain the Dracula craze in cinema that took shape around the years 1960-1970?

--

Dracula movie releases (1895-2022). Source : The Movie Database (TMDb). Graphic: Adrien Jeanrenaud.

--

Dracula movie posters (1895-2022). Source : The Movie Database (TMDb). Graphic: Adrien Jeanrenaud.

Dracula through its posters

The film that starts the cycle for the decades 60-70 could be Horror Of Dracula (Terence Fisher, 1958) in which Christopher Lee takes on the role of Dracula for the first time. The British actor had previously played the role of the monstrous creature of Dr. Frankenstein in Terence Fisher's 1957 film. The director asked him again for a horror story.

Christopher Lee played the role of Dracula ten times, thus imposing Dracula in the popular culture.

The following years, the productions on the subject are linked. In Italy, Greece, Pakistan, Japan, Mexico, Spain, France, Indonesia, among others, Dracula films are everywhere.

It is quite possible that the brilliant actor Christopher Lee has set the tone for a cycle in favor of Dracula.

But how can we approach the Dracula films without spending hundreds of hours watching them? How do you understand the production's intentions and the visual identity that unfolds around the film at a glance? Movie posters can help.

The tone of the posters

Film posters are produced so that the audience understands the main issues of the film (themes addressed, film genres), while creating the the desire to rush into a darkened room. Analyzing the film posters of Dracula allows us to grasp the primary, most direct intention of the production.

The Dracula cycle of the 1960s. Posters for films released between 1958 and 1975. Source: The Movie Database (TMDb). Graph: Adrien Jeanrenaud.

This horrible head

Visually, Dracula's head seems to be a recurring motif. A pale complexion, fangs pointing downwards, from which a few drops of blood flow; a constant expression of surprise that pulls the face back; such are the main features of Dracula on the posters.

His female victims, against the background of a haunted castle

More often than not, a woman in the background recalls Dracula's victim; sometimes a haunted castle setting pops up in the background. These elements form a pool of motifs associated with Dracula, which persist in our visual memory today. The poster depicts fears that perhaps sometimes inhabit us. How can we understand that they were more specifically embodied in the 1960s and 1970s? Perhaps it is an effect of the Cold War and social movements - as well as a liberation of morals. The climate is one of suspicion. Is it the fear of the other that Dracula emphasizes on the screen?

What is the filmic genre of Dracula?

Apart from these few common traits, it is difficult to find a unity in the posters of Dracula's films.

On the color side, the disparity between the posters is visually obvious. The films in question were produced in different countries: does this mean that the visual plurality stems from the different national anchors, the different contexts for which the posters were produced? For sure, but there is more to this.

--

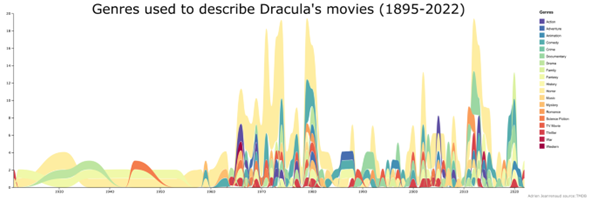

Genres of Dracula films (1895-2022). Source: The Movie Database (TMDb). Graphic: Adrien Jeanrenaud.

In order to understand the different visual strategies involved in these posters, we can look at the content of the films' production, and more specifically at the cinematographic genre that is associated with them. Generally speaking, horror is the genre commonly attributed to Dracula films. But while the horror genre is a common thread throughout the history of these films, it is not the only one present.

Until the 1960s, science fiction, fantasy and horror are the dominant film genres used to describe Dracula films.

Beyond that decade, however, the genres become more disparate. Dracula remains primarily a horror film. However, it also takes on the codes of the action film, the comedy, and even the western with the no less surprising Billy the Kid Versus Dracula (William Beaudine, 1966).

Dracula changes genres more often than one might think.

In 1968, Dracula became a cliché that could be mocked, by staging the monster of old central Europe and a character that was a priori totally different, the Billy the Kid of the American Wild West. It is, perhaps, and above all, a classic. It is adapted, re-adapted, and renewed all the more so since it is now part of a shared culture.

--

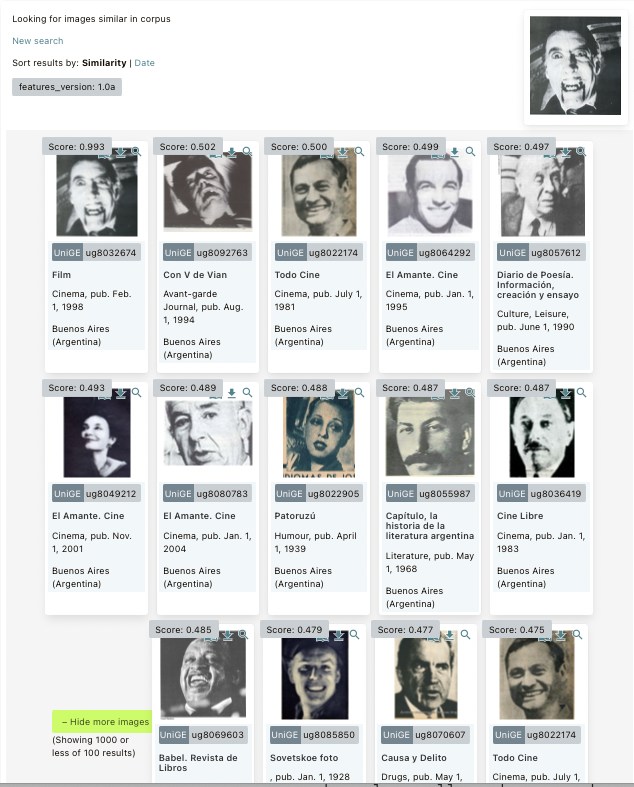

Screenshot of a search on the Explore platform, October 2022.

The multiple faces of a horror film classic

Thus, at the same time that a cycle was opened in the early 1960s, the story of Dracula took on contrasting genres. The vampire is polymorphous. He adapts to the expectations of the audiences he addresses.

Dracula crosses borders. He adapts to all cultures.

But how can we understand the constant return of Dracula throughout the world, in all genres, despite his transgressive aspect ? What if, as Matthieu Orléan says: "deep down, everyone wanted to be a vampire[4] ».

Today, the monster is still among us. At least that's what the Explore platform tells us, but also the series What we do in the shadows (Jemaine Clement, 2019-). This mockumentary follows the lives of several collocated vampires in South New York, lurking in the shadows of a timeless habitat. Some have lived for centuries, others are contemporary to us. The series flirts with several filmic genres, from horror to comedy. Unsure of their place in the world, the vampires wonder about their nature, their desires and their place in a complex society that does not have the same temporality for each person. A bit like us?

Notes

[1] STOKER, Bram, Dracula, Oxford ; New York, Oxford University Press, coll. Oxford world’s classics, 2011, p. 80.

[2] SMITH, Iain Robert, « ‘For The Dead Travel Fast’: The Transnational Afterlives Of Dracula », in SMITH, Iain Robert et VEREVIS, Constantine (éd.), Transnational film remakes, Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press, coll. Traditions in world cinema, 2017, p. 66.

[3] BORDWELL, David et THOMPSON, Kristin, L’art du film: une introduction, trad. Cyril Béghin, 2014.

[4] ORLEAN, Matthieu, « Exposition VAMPIRES, de Buffy à Dracula : du 9 octobre 2019 et le 19 janvier 2020 à la Cinémathèque française ».