What do digital ghosts dream about?

Radu Suciu

Of monks and algorithms

A few years ago, I did a research trip to the Escurial library. The catalog of this library located in the mythical monastery of Philip II was then accessible only in paper form, on handwritten paper cards. To order a document, one had to copy the information from the card onto a reservation form. One day, when the monk librarian - a small, elderly man, dressed in black and not very talkative - came back with the book I had ordered, I was surprised to find that it was not the document I had expected. The book that was returned was much more interesting. When I ordered, I thought I knew what I wanted to see; I knew what I was "looking for". But the error in the delivery of the book (for which I was responsible, having probably mistaken a number for another) allowed me to find what I was not looking for.

The experience of searching through Explore – the image search engine of the Visual Contagions project that ranks millions of images by similarity - is sometimes similar to what happened to me at the Escurial.

When I give the algorithm a starting point (in this case, an image for which I am hoping to find proofs of its circulation), I do so with an intention of exhaustiveness: the hope that the analysis of lines, patterns, shapes reduced to formulas, will give a perfect result; more precisely, the hope that the machine will find exactly the same image as mine, reproduced again and again throughout the corpus.

But we are not there yet: the algorithmic analysis (of Explore, as well as of many other similar digital research tools) is still fragmentary, approximate and incomplete. But it is precisely because it is shaky that it has the capacity to surprise us. The results unfold like digital spectra on a Halloween day.

An unexpected image appears, like a ghost.

And the image that we did not expect to see glows with a new aura, a digital aura. Many images discovered through Explore have not been consulted for decades, if not centuries. Now they are extracted by the algorithm and brought back to the light of the screens, like ghosts. Their digital reproduction reaches the status of a singular work: it is both the copy of the original stored in a place where it was never seen, and its digital avatar that can circulate freely, ad infinitum. But it also has the aura of surprises coming from the depths of time.

The algorithm reinjects serendipity into the laboratory of the historian, or the artist, or any curious person who lingers and uses it.

Algorithms, instead of allowing us this arrogance which would bring the claim of exhaustiveness, reserve us oblique, somewhat puzzling, and yet captivating discoveries.

Some ghosts from our machines

The ghost of Zidor

I came across, by pure "algorithmic" chance, this ghost story published in « La Jeunesse illustrée » on November 1st, 1903. The magazine in question used to publish educational comic strips.

Bob, a city boy, who has come to spend a vacation in the country, teaches his cousin Zidor that there is no reason to fear ghosts or owl calls. Brave and skillful, he disperses some popular beliefs and restores order in the village terrorized by a ghostly apparition. Bob reminds his cousin "that one always takes advantage of the credulity of the ignorant, that's why one must work and learn". ChatGPT couldn't have said it any better!

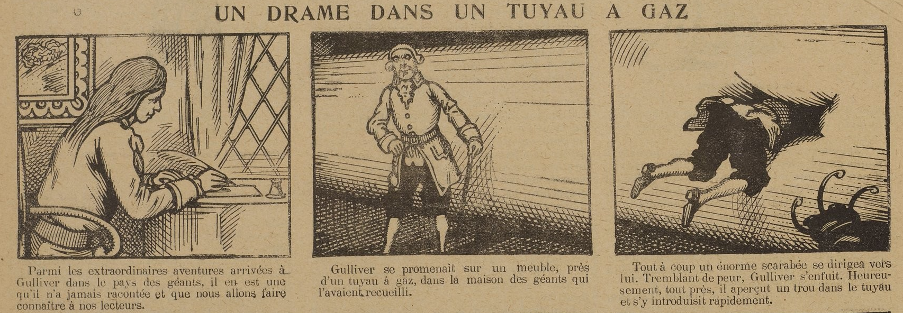

Gulliver in a gas pipe

In the pages of the same magazine, Gulliver's adventures are brought up to date. On December 29, 1907, Swift's famous sailor gets lost in a gas pipe, chased by a beetle. No doubt in order to make children aware of the dangers of gas pipes and burners, Gulliver is transposed into a modern context.

Given the energy supply difficulties predicted for the winter of 2022, the digital spectre of "Drama in a Gas Pipe" will frighten children and adults alike.

The ghosts of the machine are as much ghosts of the past as of today.

__

La Jeunesse illustrée, December 29, 1907, p. 4. Available on Gallica.

The evil eye

The images extracted by our algorithms are sometimes assembled in strange successions which, although mathematically explainable, are surrounded by a mysterious atmosphere.

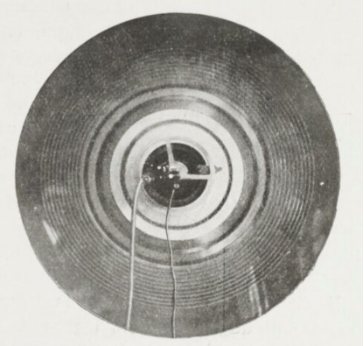

Go to Explore and look, for example, at the repetitions of this eye (figure 1).

The algorithm will do its best to track down the exact occurrences of the same image (in this case an advertisement for glasses). But others will be added, by a kind of algorithmic neighborhood (the similarity "score" decreases as you scroll through the results: the similarity is not very high anymore, but similarities are still possible).

It is no longer eyes, but rounds or medallions, plates, trays that arrive on the results page.

I almost involuntarily confront this spill of images with my own mental "database".

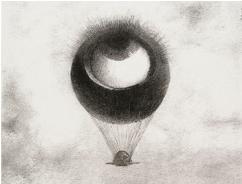

I immediately think of the "vulture's eye", the Evil Eye – of Edgar Alan Poe's short story nd, by ricochet, recalling Odilon Redon's vaporous eyes , I discover the one he had drawn to illustrate this very story of horror by Poe.

__

Odilon Redon, The Eye, like a strange balloon heading towards infinity, 1882. MoMA, New-York; The Tell-Tale Heart, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, Wikimedia Commons.

--

--Screenshot of the results of an Explore search.

--

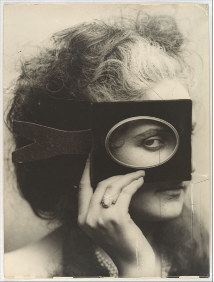

Then I think of the eye engraved by M. C. Escher in which a skull and crossbones is reflected, and I come across Pierre-Louis Pierson's Scherzo di follia: in profile, the Countess of Castiglione is looking at me through a passe-partout that encircles her right eye.

--

Pierre-Louis Pierson, Scherzo di Follia, 1861-1870, paper print 1930. The Metropolitan Museum, New York.

--

Will I soon find in Explore an image taken from the macabre scene of The Andalusian Dog, the 1929 surrealist film collaboration between Salvador Dali and Louis Buñuel, which opened with the gruesome scene gruesome scene of a razor-bladed eye?

Or this emblem by the Italian humanist Andrea Alciato showing an eye that opened in the hollow of a palm and hovers over the world? The emblem illustrated, literally, the adage of the manus oculata according to which it is always good to use caution and temperance. Seeing is believing.

Seeing is believing?

In any case, the construction of knowledge increases as we see again and again, and belief is shaped as we go along. This kind of exploratory journey is twisted and winding, but never sterile. The results offered by Explore are renewed as soon as I change my starting point for the similarity search. If the machine brought back many advertisements for glasses, it also brought back images that echoed those that thematize a haunting: the haunting of being observed, scrutinized, spied upon, or even the haunting itself. Will the cold and recalcitrant electronic eye of HAL9000 in Space Odyssey soon appear in my results? This Halloween, I see it everywhere. Is it hiding behind this image excavated by Explore and whose contours have deceived the algorithm, and me as well?

__

La revue aérienne, 25 décembre 1909. Available Gallica.

This image is however not HAL9000's "evil eye", nor that from Poe. It is simply the image, ultra-modern for the time, of an aircraft engine. Published in the Revue Aérienne on Christmas Day 1909, it represents an aeronautical machine and this proximity to frightening eyes makes me think that these technological novelties unnerving to some, while fascinating others.

What do digital ghosts dream of, then?

About anything and everything, always arbitrarily (why this image rather than another?), but never without good reason, neither for the better nor for the worse. Just as the proximity of words or associations of ideas can generate stories, so images associated by their visual proximity give rise to new interpretations, new questions, and sometimes new ways to answer them. This is serendipity. The conclusions drawn from these connections will, of course, always be those that we want, from the images and ideas that we have found most meaningful, and also from our own previous culture. From one visual echo to another, the results of Explore, whether relevant or not, will have reopened the dusty cupboards of my own memory. "Whenever [the eye] fell upon me my blood ran cold".