Skeletons in atlases

Radu Suciu

Where do the skeletons that dot the streets of our cities come from, as Halloween and the Christian feast of the dead on November 2 approach? They cross several iconographies that have sprinkled the illustrated periodicals of the first XXth century, and before them the imagery of the modern era: from the flayers of ancient times to the anatomical plates of modern medicine, through the traditional representations of death and its scythe, the skeleton has not always been necessarily (and is not always yet, far from it) a reference to death and the fear it brings us. Investigation along the VisualContagions/Explore platform.

A skull out of an eye

Explore, has we have seen, is as much a research tool as an atlas in the tradition of Aby Warburg's Mnemosyne. It makes us witness unexpected assemblages not only of images, but of all sorts of moving ideas, intellectual paths and aesthetic affinities. It is a tool with variable geometry, with irruptions of images that the algorithm provokes and summons, we don't really know why. A bit like an oulipian poetry generator, Explore serves as an idea activator.

When, in an earlier part of this episode, I was trying to understand the genealogies of the drawing of an eye, Explore made me discover in turn advertisements for eyeglasses, some astonishing drawings from avant-garde magazines, as well as prototypes of circular engines designed for the aeronautical industry at the beginning of the 20th century. Then, without warning, the eye changed, for a brief moment, and only once, into a skull, lying on its side.

--Figure 1: Excerpt from Explore results.

Vesalius' dissected bodies

Halloween obliged me to start exploring the skull and crossbones. I went in search of all sorts of mortuary illustrations through the immense heterodox corpus of 19th and 20th century magazines that Explore lists and segments.

Several great classics emerged, such as this skeleton

of Vesalius, reproduced in the pages of the magazine Formes in March 1931.

The author of the Formes article was obviously impressed by the famous flayed figures in this Renaissance anatomy treatise - all staged and animated, so to speak. It was a good opportunity for him to complain about the soulless illustrations of modern medical-scientific treatises:

We are a hundred cubits above our pale modern medical treatises, whose cold, flat plates speak only to the mind without moving our soul, without touching any fiber of our being. Here [in the treatise of Vesalius], they are great paintings revealing the organic and palpitating mystery of humans, it is the whole human and superhuman drama that these characters play, skeletons, flayed, phantoms of nervous networks (...).

--Pierre Mornand "Corporis Humani Fabrica of André Vésale", Forms, no 13, March 1931, p. 48 - 49

--André Vésale, De Humani Corporis Fabrica, 1543, reproduction published in the journal Formes, March 1931. Library of the INHA, Paris. Coll. J. Doucet.

But the algorithm, through the involuntary poetry of the machines, passes cheerfully from frightening forms to branches of trees and flowers, or to décorative contours. Vesalian skins are thus displayed next to the bones of a sauropod dinosaur from an article published in March 1905 in the Revue coloniale…

It is the involuntary poetry of machines: a corpse becomes a plant, bones change into flowers and a skull into a star of the sky.

Skeletons revealed, skeletons explained, skeletons tamed

Poetry only? And only by chance? Perhaps there is also a propitiatory tendency that reveals itself here, and that the algorithms discover by bringing together these motifs and images that were indeed conceived by people. Death scares us. If the skeleton allows to represent it in the most concrete and direct way, since it represents the inevitable end to us all, it is also a way to study it, to represent it, to put it at a distance - to tame it perhaps.

By studying, one tames it.

In this popular science article writen by Dr. Cabans in 1900 in the Revue des revues, the skeleton is annotated by arrows that show the points of "artificial" growth of man.

In teaching, one rationalizes.

Here, the skeleton resurfaces in history magazines, to illustrate and document bones found in archaeological digs, or in this 1925 popularization magazine: “Le dessin à l’école et dans la famille: revue d’éducation esthétique”.

--

Le dessin à l'école et dans la famille: revue d'éducation esthétique, avril 1925, p. 65. Heidelberg Historic Literature.

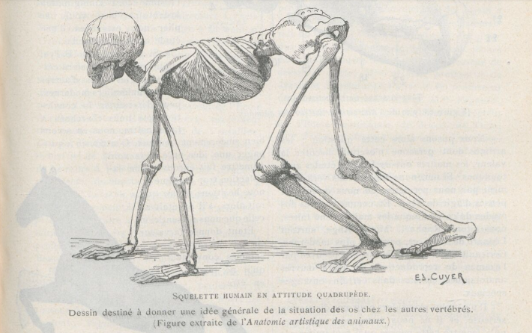

While here, finally, it became a tamed skeleton, on all fours. It shows artists how the human form would look in an “attitude quadrupède”. Published in a review on the occasion of the publication of the Anatomie artistique des animaux, a book by Edouard Cuyer, professor of anatomy at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Rouen, this ridiculous skeleton completed the cycle of de-dramatization: on all fours, death is ridiculous.

__

Le moniteur du dessin,February 15, 1903. no 11 (71), p. 163. Gallica.

Why represent death, if not to become familiar with it? By dissecting the skeleton in all possible postures, by organizing it in atlases, one part after another (bones, skull, front and side views), one posture after another, our predecessors were better able to tame the fatal destiny of every human person. Images of skeletons seem to have progressively deserted the pages of twentieth-century periodicals, as the printed medium was no longer the most important one for circulating images, nor for conveying a collective approach to taming death. Is this the reason why, after 1950, we see skeletons and monsters colonizing another medium for image circulations, the cinéma ?