Eating less is healthy thanks to gut bacteria

Mice with a lower calorie intake live longer and are both healthier and leaner. A possible path towards new obesity treatments.

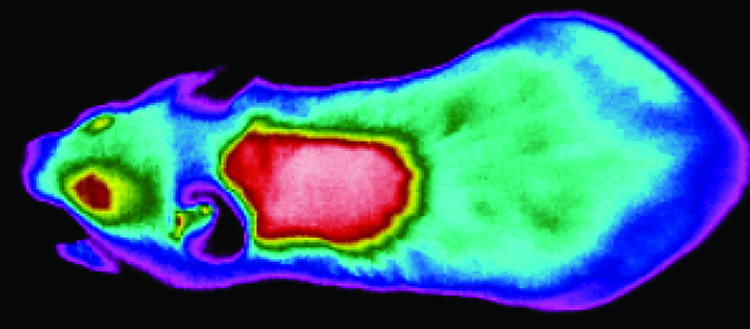

Infrared image of a mouse. The technique was used to show how calorie-restriced mice are better able to cope with low temperatures.

An international team led by researchers from the University of Geneva (UNIGE), Switzerland, and funded by the SNSF, may have found the reason for this positive effect: much of it is down to gut microbial communities and how they affect the immune system. The researchers also found compounds that mimic caloric restriction and may transform obesity treatments. Reducing the intake of calories by up to 40% has long been known to have a beneficial effect on animal health: the animals live longer, blood-sugar levels drop faster, and they burn more body fat. According to this research published in Cell Metabolism, many of these changes in the body are brought about by gut bacteria.

The international team led by SNSF professor Mirko Trajkovski, Department of Cell Physiology and Metabolism from the UNIGE Faculty of Medicine, restricted the calorie intake of mice for 30 days and found an increased amount of beige fat, a type of fat tissue that burns body fat and contributes to weight loss. Interestingly, when they transferred the caecum microbial communities from the calorie-restricted mice to other mice raised and still living in sterile conditions (i.e. without microbes in their gut), the receiving animals also developed more beige fat and were leaner despite eating normally. So the change of the microbiome alone created health benefits for the mice.

When analysing these microbial communities, Trajkovski’s team found that the gut bacteria of mice on a calorie-restricted diet produced lower levels of a toxic molecule called Lipopolysaccharide (LPS). When the LPS-levels were reconstituted to normal levels in the blood, the mice lost many health benefits of the diet.

New compounds may help in treating obesity

The bacterial LPS molecule is known to trigger an immune response by activating a specific signal receptor known as the Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4). Experimenting on mice with genetically modified immune cells lacking this receptor, the researchers were able to mimic the effect of the caloric restriction. “Clearly the immune system not only combats infections, it also plays a key role in regulating metabolism,” says Trajkovski. Apart from more beige fat and weight loss, the mice react better to insulin, their livers process sugar and fat in healthier ways and the mice are better equipped to withstand colder temperatures. “This is turning into an entirely new field of research,” says Trajkovski.

Having dissected the mechanism behind caloric restriction, the researchers set out to test two compounds: one of them directly reduces toxic LPS production by the bacteria and the other blocks the TLR4 receptor that receives the LPS signal. Both had a positive effect on the mice that was similar to that of eating less. “It may one day become possible to treat obese people with a drug that simulates caloric restriction,” says Trajkovski. “We are currently investigating the precise changes in bacterial communities, and we are also testing other compounds that reduce LPS production and signalling.”

The study was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF), the European Research Council (ERC) the Clayton Foundation and the Louis-Jeantet Foundation and conducted by researchers from the University of Geneva, AstraZeneca IMED Biotech Unit in Gothenburg (Sweden) and Inselspital Bern.

30 Aug 2018