Immune 'hijacking' predicts cancer evolution

Published on

A team from UNIGE reveals how the 'hijacking' of neutrophils, a type of immune cell, promotes cancer growth and could provide insights into disease progression.

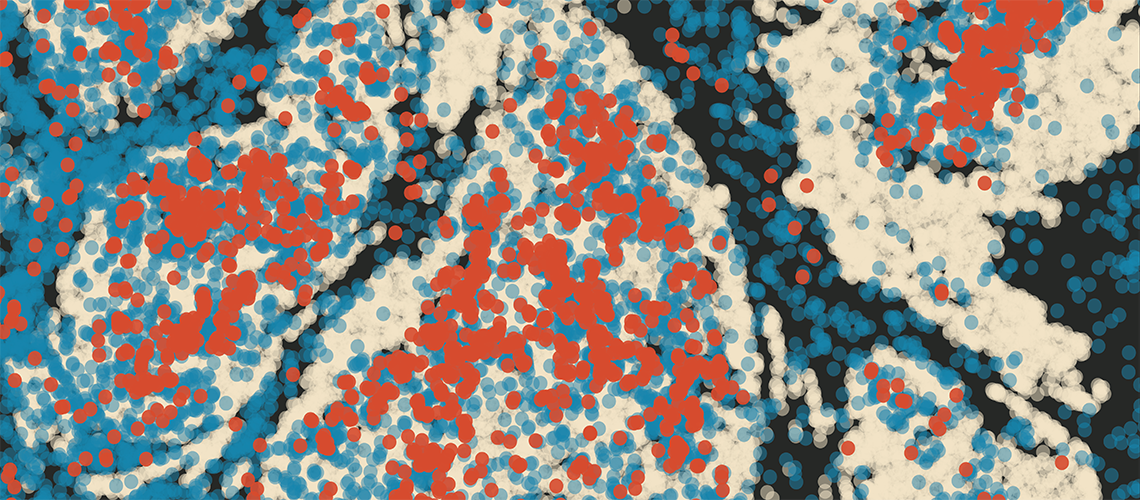

Predicting tumour progression is one of the major challenges in oncology. Scientists at the University of Geneva (UNIGE) and the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research have discovered that neutrophils, a type of immune cell, undergo reprogramming when they come into contact with the tumour ecosystem and contribute to its progression. They then produce a molecule — the chemokine CCL3 — which promotes cancer growth rather than fighting it. This mechanism appears to be a major variable in tumour biology and could serve as an indicator of disease progression. These findings are published in the journal Cancer Cell.

A tumour is not just a cluster of cancer cells but develops within a complex ecosystem where different cell populations interact. "One of the difficulties lies in identifying, in an environment we are only now beginning to understand, the elements that truly influence the tumour's ability to grow," explains Mikaël Pittet, full professor in the Department of Pathology and Immunology and at the Translational Research Centre in Onco-Haematology (CRTOH) at the UNIGE Faculty of Medicine, and member of the Lausanne Branch of the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, who led this work.

"In 2023, we showed that the expression of two genes in macrophages is strongly linked to disease progression. This constitutes a simple but informative variable for understanding tumours and anticipating their trajectory. Our new study highlights a second variable, this time involving another population of immune cells: neutrophils."

We discovered that neutrophils recruited by the tumour undergo a reprogramming of their activity.

A deleterious reprogramming

Neutrophils represent one of the most abundant populations in the immune system. They typically constitute the first line of defence against infections and injuries. In the context of cancer, however, their presence is generally a bad omen. "We discovered that neutrophils recruited by the tumour undergo a reprogramming of their activity: they begin producing a molecule locally—the chemokine CCL3—which promotes tumour growth," explains Mikaël Pittet.

An experimental and bioinformatics challenge

"Neutrophils are particularly difficult to study and to manipulate genetically," explains Evangelia Bolli, co-lead author of the study and responsible for its experimental component, then a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Pathology and Immunology at the UNIGE Faculty of Medicine, now a postdoctoral researcher at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard. "We combined different approaches to control the expression of the CCL3 gene specifically in neutrophils, without inhibiting it in other cells. A delicate exercise!" The result? Without CCL3, neutrophils lose their pro-tumour action. They retain their physiological functions in the blood and can even accumulate in tumours, but no longer adopt the deleterious reprogramming previously observed.

To complete their analysis, the research team re-examined data from numerous independent studies. "We had to innovate to detect neutrophils more accurately," explains Pratyaksha Wirapati, co-first author and bioinformatics specialist. "Their low genetic activity often makes them invisible using standard analysis tools. By developing a new method, we have been able to show that, in many cancers, these cells share a common trajectory: they produce large amounts of CCL3, which is associated with pro-tumour activity."

Towards a potential prognostic marker

With CCL3, Mikaël Pittet's team has now identified a new variable likely to provide information on tumour progression. "We are deciphering the 'identity card' of tumours, by identifying, one by one, the key variables that determine the evolution of the disease," explains the researcher. "Our work suggests that there is a limited number of these variables. Once they are properly identified, they could help better tailor the management of each patient and, ultimately, offer more effective and personalised care."

Contact

Mikaël Pittet

Full Professor

ISREC Foundation in Immuno-Oncology

Department of Pathology and Immunology

Translational Research Centre in Onco-Hematology (CRTOH)

Faculty of Medicine

UNIGE

Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research

+41 79 73 73 295

This research is published in

Cancer Cell

DOI:10.1016/j.ccell.2026.01.006