Cells rely on their crampons to avoid slipping

Researchers from UNIGE identified a new function for a protein that helps cells to sense their environment and dock at their proper place in the body.

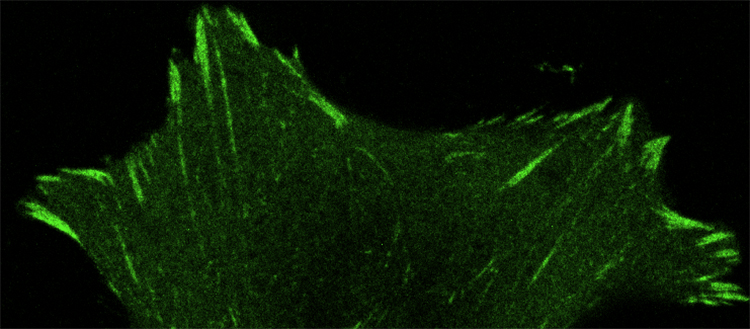

Through the action of paxillin, cells form focal adhesions (in green) to anchor themselves in their environment. © UNIGE

Each human being is made of billions of cells. In order to ensure his survival, cells must coordinate with each other and attach in the right place to perform their tasks. Scientists from the University of Geneva (UNIGE), Switzerland, in collaboration with the University of Tampere in Finland, have highlighted the key role of a protein called paxillin, which enables cells to perceive their environment and anchor at the right place with the help of cellular “crampons”. Indeed, without functional paxillin, the cell is unable to attach properly and slips continuously. These results, to be read in the journal Communications Biology, shed new light on how cells adhere or migrate, mechanisms essential to the good functioning of our organs, but also involved in the development of metastatic tumors.

To ensure our survival, each cell performs specific functions in coordination with their neighbours. In such a dynamic system, the migration of cells and their anchoring at the right place are essential. But how do cells manage to coordinate with each other? Scientists have long believed that cells communicate mainly through chemical signals, such as hormones. However, recent discoveries suggest that mechanical signals play a major role in cell coordination. “This is why we started to study the ability of cells to decipher and respond to their physical environment”, explains Bernhard Wehrle-Haller, Professor at the Department of cell physiology and metabolism at UNIGE Faculty of Medicine. “Especially as it could help us to understand how cancer cells use these mechanisms to invade other organs and form metastases.”

From a mechanical cue to a biological signal

When a cell has to move, it “senses” its environment with the help of proteins on its surface, the integrins. When the cell detects a suitable location, a complex network of proteins, called focal adhesion, is then set up to form cellular crampons that anchor the cell to its environment. “But how is this anchoring mechanism regulated? This is what we wanted to find out,” explains Marta Ripamonti, researcher in the laboratory of Prof. Bernhard Wehrle-Haller and first author of the study.

By studying paxillin, one of the many proteins that make up these crampons, researchers were able to unravel the mystery. “We knew that this protein played a role in the assembly of focal adhesions, but we didn’t expect it to be the key regulator”, says Prof. Bernhard Wehrle-Haller with enthusiasm. Without functional paxillin, cells are unable to anchor, regardless of the suitability of their environment. In addition, paxillin has also the function of informing the cell that anchoring has taken place correctly, thus transforming a mechanical response into a biological signal that the cell can understand.

Disrupting the crampons to prevent metastases?

These in vitro experiments highlight the major role of paxillin in the migration and adhesion of healthy cells, but they could also be a starting point for a better understanding of cancer development. “It is indeed likely that cancer cells use paxillin to find a place that enhance their survival. Would it be possible to block this mechanism in tumor cells and prevent the formation of metastases? Yes, we think so! ” concludes Prof. Bernhard Wehrle-Haller.

Watch a cell without crampons slipping continuously.

29 Mar 2021