A Living Discipline: Mathematics and Its Expanding Horizons - Interview with Michelle Bucher

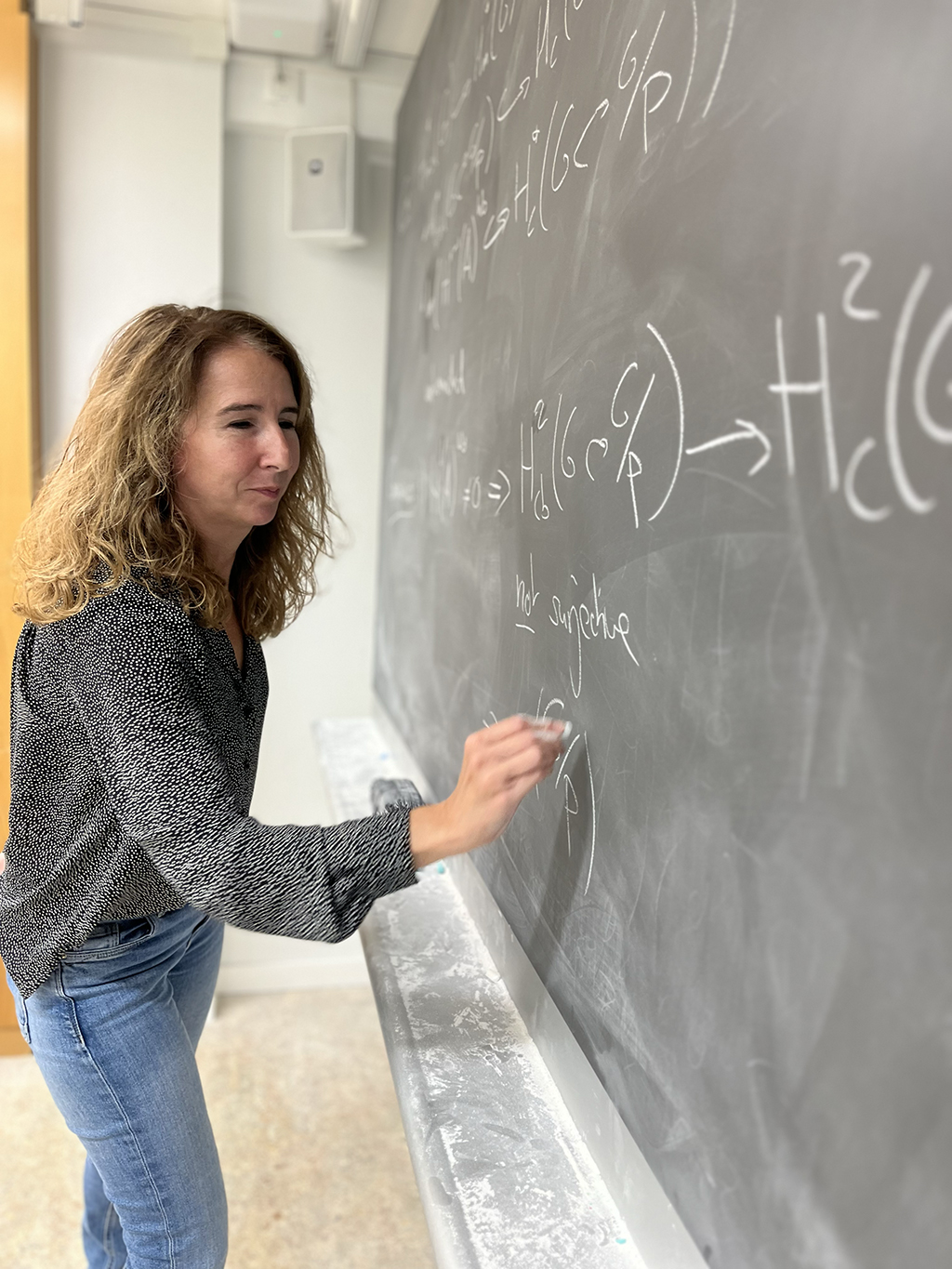

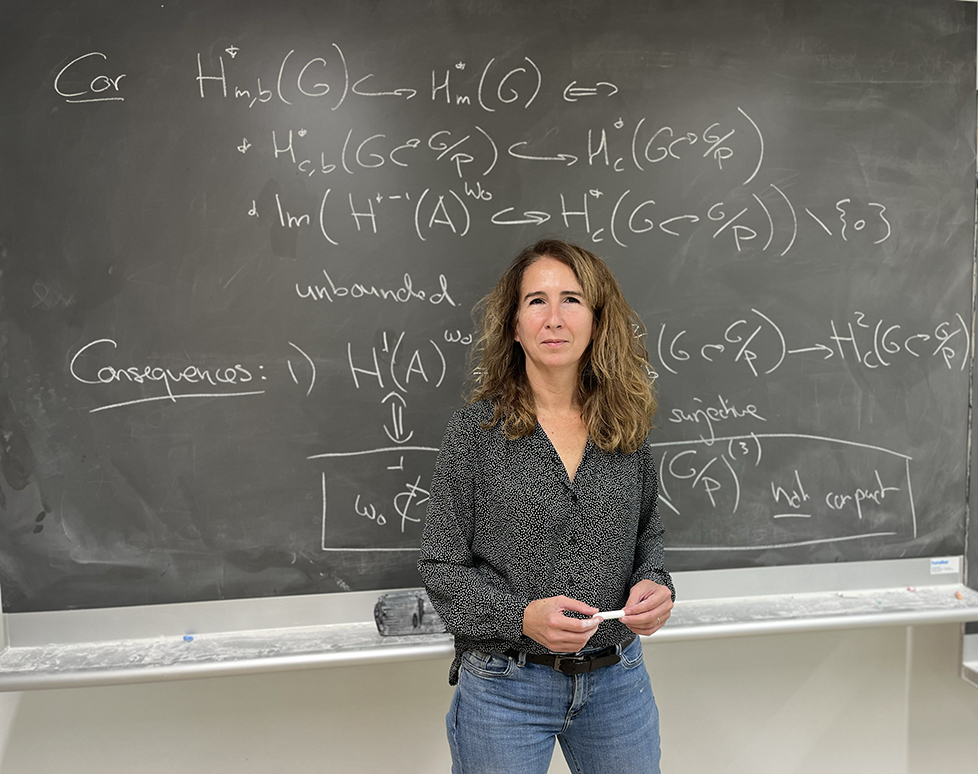

Michelle Bucher has had a path through mathematics that will be familiar to many people, and yet is full of anecdotes and experiences that make it unquestionably unique to her. She completed degrees at the University of Geneva and ETH Zurich, before going on to complete postdocs around the world, which she described as “the most difficult part of a young researcher’s career” owing to the uncertainty and short project lengths. She got tenure track at KTH Stockholm before taking a FNS professorship at Geneva via a postdoc at EPF Lausanne, and is now a Senior Lecturer at the University of Geneva. Of course, she admits the best part of her job is the research, but she greatly enjoys the opportunities to teach and interact with students - adding that the immediate rewards that come with teaching can sometimes be more satisfying than the occasional “Eureka!” moments one has when doing research.

“I love seeing the stars in the students’ eyes when they learn a new concept”

Whether it’s undergraduate classes, more advanced optional classes or research seminars, she thrives when presenting mathematics - from the very fundamental to the arcane details of her own work. Her favourite, though, is working with first-year Bachelor students - “a big audience of young people that are new to the field”, in her own words. She recalls her own first year and how it felt like her brain was being reset, and takes great joy in initiating the same in the new generations of scholars at UNIGE.

Her own choice to study math happened by chance: Michelle knew she was good at the subject, but wasn’t certain what she wanted to do, and picked mathematics as a solid place to start. For her, the moment when she realised that she wanted to do research as a career was not an instant in time, but rather a continuous process and the culmination of various motivating factors. She enjoyed the subject, her professors encouraged her to stay in the field, and it was a natural step forward. Not everything was perfect: at one point, she found herself limited in options and applied for a single position, with the mindset that she would quit math if she didn’t get it. She laughs as she recalls the anecdote: she isn’t sure if she would have followed through with that decision. Thankfully she didn’t have to, as she got the job.

Explaining what you do to a layperson is always a challenge, but Michelle is more than up to the challenge.

“I work in the intersection between geometry and topology, and one concept which comes up regularly in my work is called the Euler characteristic”.

You may have already heard of the famous equation that relates the faces, edges and vertices of a polyhedron: F - E + V = 2. Where does this come from, though, and what is the significance of the 2? Michelle Bucher asks us to imagine “projecting” the polyhedron onto a sphere - drawing 8 points, and 12 lines connecting them - and remarks that having the sphere as a basis on which to draw our polyhedra makes proving the combinatorial fact that F - E + V = 2 much easier. Furthermore, it’s now easy to see that the value 2 is intimately associated with the sphere - if we change the surface we’re projecting onto (for example, a torus, or donut) we’d instead get a different value (namely, 0).

The fact that the value is equal to 2 for the sphere has further implications: one, says Michelle Bucher, is the famous “hairy ball” theorem (you cannot comb a ball covered in hair without creating a cowlick - or, in mathematical terms, “there is no nowhere vanishing vector field on a sphere”.) And why restrict ourselves to two dimensions? We can stretch our analysis to higher dimensional objects as well - with a little imagination and a lot of math! She might feel right at home with topological invariants, but during her Master’s thesis, she did a lot of work in geometric group theory, and admits she returns to it from time to time. Mathematicians don’t have to restrict themselves to their specialisation. Her work has had applications in a variety of fields, though she considers “the most exotic application to have been in combinatorics, in counting problems.”

When it comes to research, many wonder whether certain branches of mathematics offer more opportunities than others. According to Michelle, open questions can be found everywhere, even in fields often considered “closed,” such as linear algebra or general topology. “I feel many people get the wrong impression of some subjects taught in the first or second year of university – those courses make them seem so concise that it looks as though they extend only as far as what has been taught.” In particular, nearly every branch reveals numerous applications as time goes on: “for example, linear algebra is very active right now, applied to various algorithms for data processing and machine learning.” Of course, at times certain topics become trendier than others, meaning that at a given moment more people focus on them – sometimes because they offer more applications in connection with current technology advancements – but that does not mean they have more to offer overall. Although Michelle Bucher is a pure theoretician – she has only ever collaborated with fellow mathematicians and never with researchers from other fields – she considers the applications of mathematics, and the new fields they generate, to be truly beautiful. The rise of branches combining mathematics with sciences such as biology or chemistry (such as mathematical biology or mathematical chemistry) represents highly interesting projects, as long as they are not motivated by funding solely: indeed, universities tend to devote far more resources to research that involves applications. Ultimately, she sees mathematics as a living discipline, one that continually expands its horizons – whether within its own foundations or through the bridges it builds to other sciences.

Why do research, as opposed to working in industry? Michelle Bucher offers two answers. “On a personal level, you should do it if you like it. But in general, research in fundamental mathematics is important and ideas should develop freely, without considering what the applications might be down the line - and many results that are today considered useful fall into this category.” She lists knot theory as an example - both useful in other areas of mathematics (topology, in particular for studying three-dimensional manifolds) and other sciences (for instance, in biology, when studying the structure of DNA). And where does Michelle find new challenges at the end of a long paper or research project? She describes it as a continuous process: the end of one question opens doors to a world of new inquiries. How can you generalise your result? What other corollaries follow from your work? Are there any natural conjectures to make? Mathematics is collaborative, and colleagues are a valuable source of inspiration for what to do next.

Over the past ten years – and especially during the pandemic – the ways of communicating in mathematics have changed drastically. Instead of always having to travel across the world to take part in a conference on a topic of interest, it has now become possible to share ideas or attend such events online. In Michelle’s opinion, although it is sometimes convenient to call a colleague over Zoom to discuss a topic or a question, in-person conferences should forever remain a major part of a mathematician’s work life. “It’s not only about the talks themselves or the few questions you might ask the lecturer after them, it’s also the minor interactions you have at coffee breaks when you’re discussing the talks, and then all of a sudden you have a new idea, or another question just pops. Or you could be talking to someone about what you’re currently working on, and they could ask something you haven’t thought of or mention they know someone working on a related problem.” As for collaborations, she believes that video calls can certainly be helpful and speed up progress, but they typically begin in person, where the main ideas are first discussed and developed, in the same room, with the blackboard and over coffee. Also regarding attention, it is naturally much easier to concentrate during an in-person lecture, where there are no distractions or temptations to take a “quick break to grab a snack.” Reciprocally, when teaching or giving a talk online, you cannot see your listeners’ reactions in the same way as when you are physically in front of them. “So overall, it’s just not as pleasant” – says Michelle Bucher. Regarding her own travels around the world during her studies, she sees a great value in visiting many places and learning from the way things work at different math departments around the world. “It can happen [that someone passes their entire career in one institution] but I think it’s important to go abroad, to get ideas from other universities, see how teaching can be done differently.”

When asked whether she believes we should fear AI gaining dominance in mathematical fields, Michelle Bucher replies that we should rather learn to coexist and work with AI instead. Just as we first adapted to calculators and then to computers, we can adjust to AI so that it handles tasks we theoretically know how to do but find tedious or simply lack the time and memory to complete. “I definitely think it can be a big help,” she says. “It will in my opinion never be more than just a tool — we always need, and will always need, a human brain to guide the machine and check its work. I do not think that there’s any risk of it replacing us”. Ultimately, it’s not a threat but a powerful tool that, when guided by human insight, can enhance our capabilities without ever replacing the need for human reasoning.

The question was: “Is it possible for two different and incoherent theories to be built on the same base?” Michelle Bucher’s answer was simple: “If the logical axioms are the same and consistent, then no – and that’s what’s beautiful about mathematics. When I first entered the field, that’s exactly what I loved the most about it: everything is either true, false, or unknown; there’s no half-truth. That’s why you know that if something doesn’t add up, then there’s necessarily a mistake somewhere." Such a situation has happened to the researcher herself: “I had found that a certain invariant was equal to something like 6, which contradicted a published result, and I had triple-checked all my work. So I somehow naively sent the authors an email, suggesting that their proof might be wrong, which they naturally though politely dismissed – the thing was, I couldn’t publish my paper as long as theirs was still out there as two contradictory results cannot hold simultaneously, and not many would have believed a young inexperienced researcher. A few months later, I had identified the issue in their proof and after pointing it out, they immediately wrote a correction, and I could finally publish my results.” In research, such situations occur fairly often, but they are usually resolved quickly. “Another thing is there’s a remarkable honesty about mistakes in the mathematical community. We make mistakes, and to be honest I’m glad I’m not a medical doctor” – shares Bucher.

About a hundred years ago, building a career in science as a woman was nearly impossible. While things have generally improved with time, Michelle Bucher believes that being a woman in mathematics actually offered more advantages when she was a student than it does today. Back then, if you were bright, you would automatically attract more attention – in a positive way – than a man. Now, however, disparaging remarks abound. “So if I were to give advice to young girls, I would say: if you like maths go for it, let the passion for the subject be stronger than any discriminative comments you might get – an advice that holds for men as well as for women.”

This article was prepared for the Science Olympiad. The interview was conducted by Yuta Mikhalkin, from the Volunteers for Physics in the Science Olympiad media team. After taking part in the Olympiad herself, she went on to study mathematics at the University of Geneva.

This article was prepared for the Science Olympiad. The interview was conducted by Yuta Mikhalkin, from the Volunteers for Physics in the Science Olympiad media team. After taking part in the Olympiad herself, she went on to study mathematics at the University of Geneva.