Research

Overview

Our research seeks to understand electron transfer and catalytic mechanisms of enzymes that catalyze environmentally important reactions. With this understanding, we aim to ultimately couple them to electrode surfaces to (i) have a thermodynamic handle on electron transfer and catalysis, and (ii) apply them to new renewable energy dependent biotechnologies. Our research also informs the design of new bio-inspired catalysts. Key environmental reactions of interest are: (i) dinitrogen (N2) reduction to ammonia (NH3), (ii) water reduction to molecular hydrogen (H2), and (iii) carbon dioxide (CO2) reduction to products such as formate (HCOO–) or other hydrocarbons of value.

We primarily focus on enzymes including nitrogenases (and the related dark-operative protochlorophyllide oxidoreductsase, DPOR), hydrogenases and formate dehydrogenases. These enzymes are not commercially available. As such, our multidisciplinary research includes bacterial cultivation and protein purification, DNA mutagenesis (i.e., site-directed mutagenesis), mechanistic enzymology, enzymatic electrochemistry/electrocatalysis, and product analysis. In the case of enzymatic electrochemistry,

Our multidisciplinary research combines skills ranging from recombinant protein production to enzymatic electrochemistry to study enzymes that catalyze reactions such as (i) dinitrogen (N2) reduction to ammonia (NH3), (ii) carbon dioxide (CO2) reduction, and (iii) large metalloenzyme complexes that employ non-trivial electron transfer mechanisms. In enzymatic electrochemistry, electrodes can be electronically coupled to metalloenzymes in many different ways although the desired outcome remains the same: the electrode supplies the reducing equivalents to the reductive metalloenzyme for subsequent catalysis (or, electrocatalysis) where the corresponding current is proportional to the rate of substrate reduction by the enzyme.

Nitrogenase:

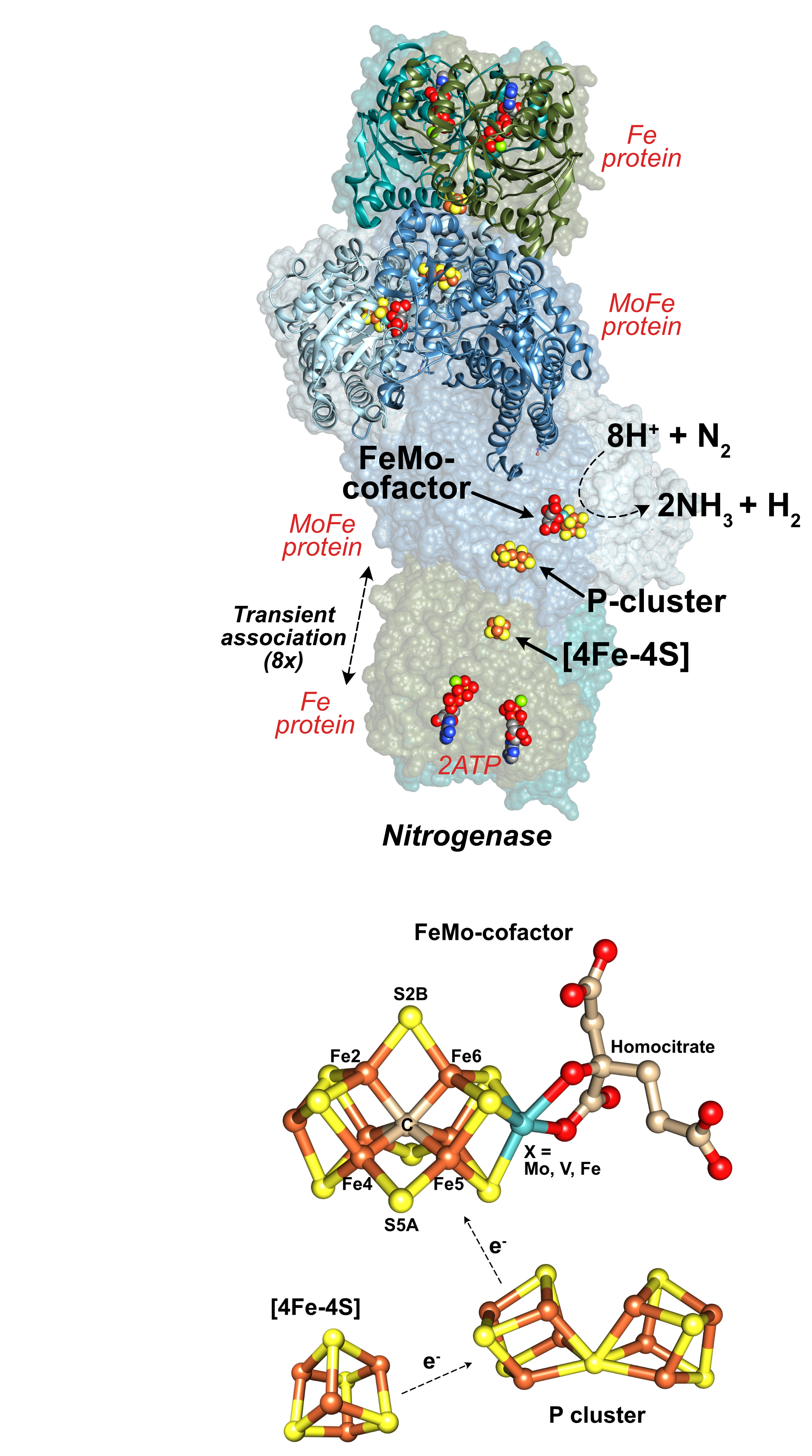

As the only known metalloenzyme capable of reducing kinetically inert dinitrogen (to produce ammonia), nitrogenase is of significant research interest. First, understanding how nitrogenase transfers electrons and hydrolyzes ATP to reduce dinitrogen (in aqueous solution) could assist the design of bio-inspired catalysts for ammonia production. The decoupling of nitrogenase from its necessity to hydrolyze ATP represents an additional valuable target. In 2016, it was shown that an electrode could be used to bypass the electron-supplying, ATP-hydrolyzing Fe protein of nitrogenase and supply electrons to the catalytic MoFe protein for substrate reduction. To this end, one of the aims of our research group is it develop advanced nitrogenase-electrode interfaces to study this enzyme's mechanism, ultimately progressing towards the deployment of nitrogenase in new biotechnologies for ammonia production. Take a look at this review of our earlier work.

More recently, we've been investigating cooperativity in nitrogenase. The MoFe protein is an (αβ)2 heterotetramer of approximately C2 symmetry with two functional catalytic halves undergoing repeated transient association with the Fe protein for successive electron delivery to the FeMoco. Why is the MoFe protein a dimer of dimers? Is this simply for increased stability/solubility of the protein? Not only. Cooperativity has been observed between the two αβ halves of the MoFe protein. Our recent research has investigated this cooperativity by (i) introducing a steric inhibitor of the Fe protein to one αβ half of the MoFe protein, and (ii) disrupting a highly conserved mononuclear metal-binding site of Mo-dependent nitrogenases (which we speculated may have been involved in transducing conformational coooperativity).

Our research receives continuous financial support from the NCCR Catalysis in Switzerland (since 2021), a National Centre of Competence in Research (Grants 180544 and 225147). We are also co-funded by a multi-PI/lead agency grant between Switzerland, France and Germany (with George Cutsail, Wenyu Gu, Victor Mougel, Markus Reiher and Tristan Wagner, SNSF Grant 10001903, 2025-2029).

Figure (top right). Representation of the nitrogenase complex. Each active dimer of the tetrameric catalytic MoFe protein contains an iron-molybdenum cofactor (FeMo-co, [7Fe-9S-C-Mo-homocitrate]) where dinitrogen and protons are reduced to two equivalents of ammonia and one equivalent of molecular hydrogen. A [8Fe-7S] P cluster within the MoFe protein is involved in transferring electrons from the reducing Fe protein, which contains a [4Fe-4S] cluster and two MgATP-hydrolyzing sites. (Bottom right). Structures of nitrogenase's cofactors, where the position colored in cyan can be a Mo, V, or Fe metal. Fe = rust, S = yellow, C = beige, Mo/V/Fe = cyan, O = red.

Dark-operative protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase (DPOR):

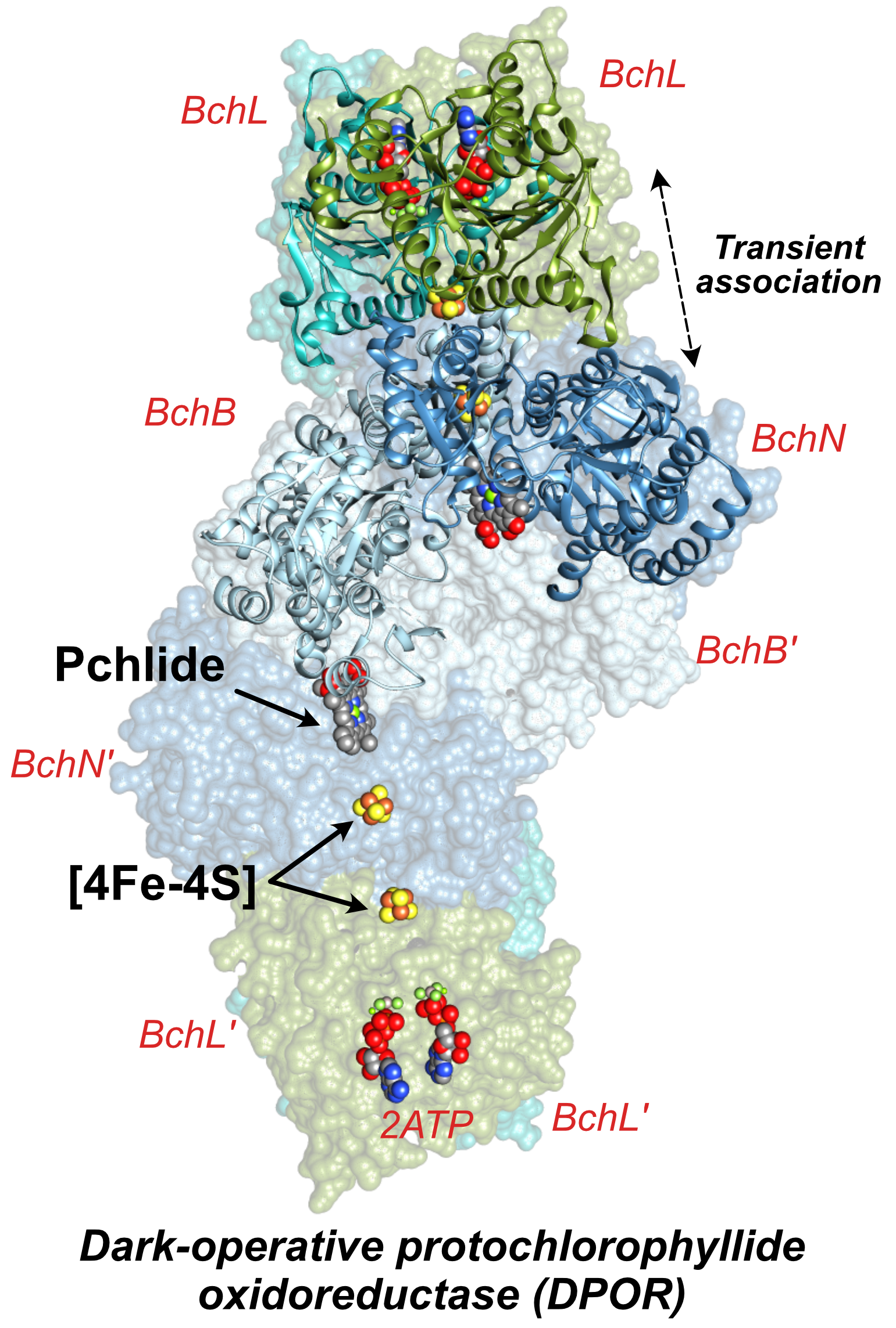

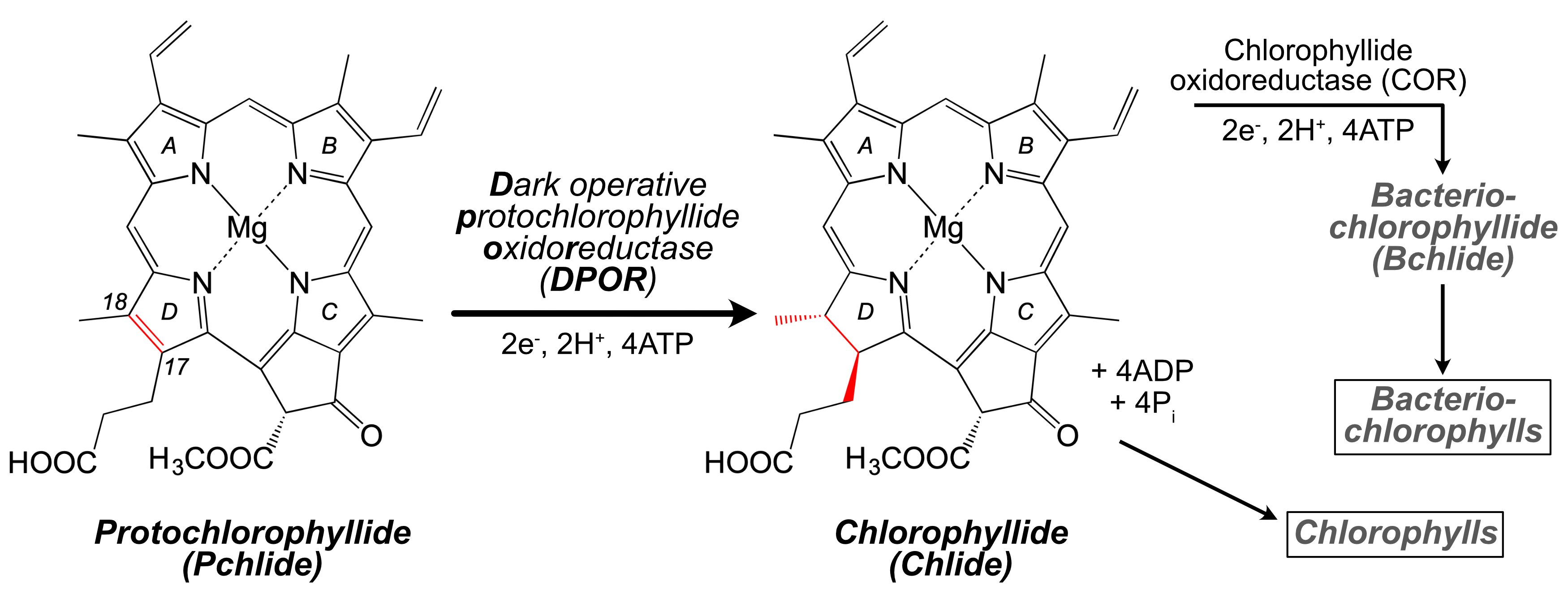

Chlorophylls and bacteriochlorophylls are organic pigments that are essential to light-harvesting organisms, produced in nature on a global scale of around 6 billion tons annually. DPOR is a complex metalloenzyme that catalyzes the light-independent 2-electron reduction of protochlorophyllide (Pchlide) to chlorophyllide (Chlide) in phototrophic bacteria, which undergoes a second 2-electron reduction to yield bacteriochlorophyllide (Bchlide). We are interested in understanding the catalytic and electron transfer mechanisms of this metalloenzyme complex, which shares a degree of homology with nitrogenase. DPOR also couples the hydrolysis of ATP to electron transfer for substrate reduction.

We have reported electron donors that are able to sustain in vitro catalytic turnover of DPOR, as alternatives to the commonly use dithionite anion.

This research was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF), grant number: 200021_191985 (2020-2024).

Figure (right). Representation of the DPOR complex. Each catalytic half of the tetrameric catalytic protein (here, BchNB) contains a [4Fe-4S] cluster that presumably aids in transferring electrons from the reducing (and MgATP-hydrolyzing) reductase "BchL", for Pchlide reduction within the BchNB protein. Being similar to the Fe protein of nitrogenase, the BchL protein contains a single [4Fe-4S] cluster in addition to two MgATP-hydrolyzing sites. Illustration prepared from Protein Data Bank file 2YNM.

Figure (below). DPOR catalyzes the 2-electron reduction of Pchlide to Chlide, at the C17=C18 double bond in the D ring of the substrate. In phototrophic bacteria, chlorophyllide oxidoreductase (COR) performs a second 2-electron reduction of Chlide to yield bacteriochlorophyllide (Bchlide).

Hydrogenase:

Hydrogenases are metal-containing enzymes that reduce protons to produce molecular hydrogen (H2, or vice versa). Thus, hydrogenases are attractive for new biotechnologies to either produce electrical energy from the oxidation of H2, or to produce H2 from renewable electrical energy (as a form of energy storage). In our research group, we typically employ hydrogenase as a model hydrogen-evolving metalloenzyme when we are developing electron mediators and/or tailored electrode surfaces for enzymatic electrochemistry. While there are 4 main types of hydrogenases ([NiFe], [NiFeSe], [FeFe] and [Fe]-only), we primarily employ the [FeFe]-hydrogenase from Clostridium pasteurianum.

More recently, we have reported on direct electron transfer to [FeFe]-hydrogenase using easy-to-make mesoporous indium:tin oxide (ITO) electrodes. We observed high catalytic activity and prolonged stability. We hypothesize that this is due to the nanoconfinement effect, where [FeFe]-hydrogenase was found to be comparatively more active and more stable on mesoporous vs. planar electrodes.

Our research receives continuous financial support from the NCCR Catalysis in Switzerland (since 2021), a National Centre of Competence in Research (Grants 180544 and 225147). We are also supported by Swiss National Science Foundation project funding (Grant 10001704, 2024-2028).

Figure (right): Representation of [FeFe]-hydrogenase from C. pasteurianum. Adapted from Protein Data Bank file 6N59.

Formate dehydrogenase (Fdh):

Formate dehydrogenases are enzymes that catalyze the reduction of carbon dioxide to formate (or formate oxidation to carbon dioxide). Fdhs can be further divided into metal-dependent Fdhs (W- or Mo-dependent) and metal-independent Fdhs (such as NAD+-dependent). We are interested in metal-dependent Fdhs as they can undergo facile electron transfer with heterogeneous surfaces (such as electrode surfaces) and catalyze carbon dioxide reduction at high rates. To this end, we are interested in developing bespoke/tailored electrode:enzyme interfaces for enhanced electroenzymatic carbon dioxide reduction by Fdhs. Selmihan SAHIN in our group was awarded a Marie Sklodowska-Curie Individual Fellowship concerning metal-dependent Fdh electrochemistry, see here.

Financial support: