Martha Jane Anderson, "The Bird Craze" (1895)

Ethical Veganism, Fashion Victims, and the Victorian "Bird Craze"

The success of the Veganuary campaign, which asks people to pledge to a refusal of meat in favor of a plant-based diet throughout the month of January, has enjoyed increasing success each year since its inception in 2014. This success has been matched by criticism of the campaign's incremental approach by "abolitionist" vegans, who object to the implication that carnism is acceptable for the remaining 11 months of the year and also the emphasis that is placed on food, diet, and human health rather than animal rights. This conflict between gradualist and abolitionist veganism can be seen in the approach taken by Emarel Freshel in her veg*an cookbook (featured here to mark Thanksgiving 2022) in contrast with vegan activism that is aligned with the intersectional values of ethical veganism. Among the wealth of information provided on its website, the charity Animal Ethics describes how "Veganism is a moral position that opposes exploiting and otherwise harming nonhuman animals. This includes what we do directly, such as hunting or fishing. It also includes what we support as consumers, which affects many more animals. ... Veganism means not consuming these products so animals are not harmed to produce them. At the heart of veganism is respect for all sentient beings. Vegans see all sentient animals as beings we should respect, not as objects for us to use."

A powerful expression of the intersectional functioning of exploitation and social injustice — with the consumption of animals at its center — came from an unexpected source at the end of the nineteenth century. In 1895, a Shaker elderess, Martha Jane Anderson (1844-1897) published in the anthology of Shaker writings, Mount Lebanon Cedar Boughs: Original Poems by the North Family of Shakers, the poem "The Bird Craze" denouncing the contemporary exploitation by the fashion industry of birds to decorate women's hats.

The United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing (known as the Shakers) was an unexpected source of vegan critique of animal exploitation because veganism was not a tenet of Shaker belief. When, in June 1843, Bronson Alcott and Charles Lane left Fruitlands for an afternoon of visiting the neighboring Harvard Shaker community, they praised the system of communal property but criticized the Shaker involvement in commercial trade and the consumption of a diet that included animal products. When the Fruitlands group disbanded, Charles Lane moved to the Harvard Shaker community for a time.

The first Shaker community was established at New Lebanon, near Albany in New York state, in 1787. According to the Shaker Museum, "At its peak in the mid-19th century, Mount Lebanon spanned over 6,000 acres and around 600 people lived and worked in hundreds of buildings. Within this central community the Shakers developed their progressive ideas on gender equality, racial equality, pacifism, communal property, the value of labor, and sustainability. They also established the now famous Shaker aesthetic of simplicity, expressed in their objects, furniture, buildings, and village planning.

Shaker communities were divided into families, typically made up of 50-100 men, women, and children. Families were self-sustaining, with their own communal laundries, kitchen gardens, agricultural operations, commercial industries, classrooms, and dwellings. The North Family [to which Martha Anderson belonged] was established ca. 1800 and served as a conduit between 'the World' and the more cloistered Church, Center, South, Upper and Lower Canaan, Second, and East Families. [See, at right, one of the sequence of photographs of the North Family property, Mount Lebanon Shaker Village, archived by the Library of Congress.] Shakers at the North Family worked to attract new members by holding a public worship each Sunday, publishing theological books and tracts, and attending gatherings in the World where there might be an opening to proselytize about their faith and life."

According to the biography provided by the Shaker Museum: "Martha J. Anderson came to the Shakers as a child; it is not known precisely when, but it is recorded that she attended the school at Mount Lebanon from 1856 to 1858. By 1860, she was living at the North Family, where she remained for the rest of her life. She worked as a tailor and made mats, and served as both an eldress and a deaconess. She was also a prolific writer. She kept a diary for a time, and wrote hymns, poems, and dozens of pieces which were published in the Shaker Manifesto. Two of these, entitled 'Health Notes from Mount Lebanon,' which appeared in the April and May, 1892 issues of the Manifesto, give a detailed description of daily life at the Shaker community in that time, including the schedule kept, activities and work engaged in, and housekeeping and health maintenance practices."

The anthology to which she contributed "The Bird Craze," Mount Lebanon Cedar Boughs: Original Poems by the North Family of Shakers (1895) represents, as a whole, an intervention in a range of intersecting social justice issues: veg*anism, animal rights, the abolition of slavery, labor rights and working conditions, women's rights and, connected especially to the latter, dress reform. The eponymous "Bird Craze" of the poem names a fashion phenomenon among the wealthy transatlantic elite of Gilded Age America when women wore real, taxidermied birds, and avian body parts (feathers, heads, skins), as ornaments, notably on their hats.

Fashion Victims and "Murderous Millinery"

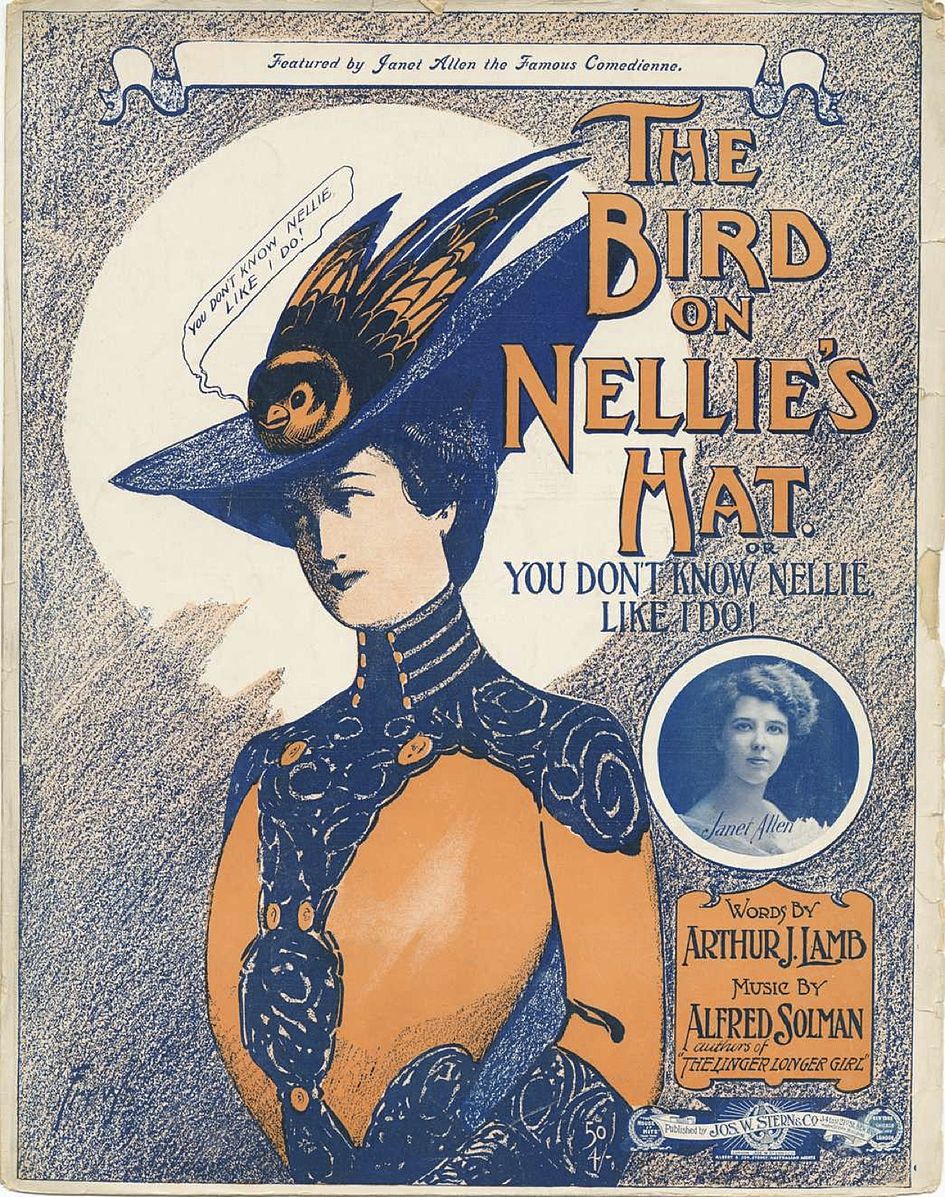

Linton Weeks, in a 2015 article for NPR, reports that: "American fashionistas were in a frenzy over feather hats. Haute headwear made from real bird plumage was seen everywhere."  The example (right) is held by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Cataloged as "Hat ca. 1890," it was designed by "Mlle. Louise" and constructed from "bast fiber, cotton, birds, feathers." The image is accompanied by the note: "Use of woven bast fiber in this hat evokes a bird's nest. The design illustrates the popularity of using real birds as millinery trim." Further examples of these hats, held by the MMA are not available for download but links to the images are provided below under "Image Credits." This fashion frenzy, Weeks continues, "was so widespread, in fact, that by 1886, writes Douglas Brinkley in The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America, 'more than 5 million birds were being massacred yearly to satisfy the booming North American millinery trade. Along Manhattan's Ladies' Mile — the principal shopping district, centered on Broadway and Twenty-Third Street — retail stores sold the feathers of snowy egrets, white ibises, and great blue herons.' He continues, 'Dense bird colonies were being wiped out in Florida so that women of the "private carriage crowd" could make a fashion statement by shopping for aigrettes. Some women even wanted a stuffed owl head on their bonnets and a full hummingbird wrapped in bejeweled vegetation as a brooch.'"

The example (right) is held by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Cataloged as "Hat ca. 1890," it was designed by "Mlle. Louise" and constructed from "bast fiber, cotton, birds, feathers." The image is accompanied by the note: "Use of woven bast fiber in this hat evokes a bird's nest. The design illustrates the popularity of using real birds as millinery trim." Further examples of these hats, held by the MMA are not available for download but links to the images are provided below under "Image Credits." This fashion frenzy, Weeks continues, "was so widespread, in fact, that by 1886, writes Douglas Brinkley in The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America, 'more than 5 million birds were being massacred yearly to satisfy the booming North American millinery trade. Along Manhattan's Ladies' Mile — the principal shopping district, centered on Broadway and Twenty-Third Street — retail stores sold the feathers of snowy egrets, white ibises, and great blue herons.' He continues, 'Dense bird colonies were being wiped out in Florida so that women of the "private carriage crowd" could make a fashion statement by shopping for aigrettes. Some women even wanted a stuffed owl head on their bonnets and a full hummingbird wrapped in bejeweled vegetation as a brooch.'"

Two major consequences of this fashion craze are reported by Linton Weeks: the emergence of local Audubon societies, which eventually formed the National Audubon Society, and a sequence of legislative instruments, like the Lacey Act of 1900, the Weeks-McLean Act  of 1913, and the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, designed to protect migratory and song birds from the immediate threat of species extinction. Robin Doughty, in Feather Fashions and Bird Preservation cites numbers extracted from London auction sales between 1890 and 1911: 1,125,000 herons and egrets (1897-1911), 50,000 kingfishers (1906-1907), 152,000 hummingbirds (1904-1911), 155,000 birds of paradise (1904-1908), noting that, in 1888, "a single London dealer admitted that he had sold 2,000,000 of small birds of every kind and color" (30). Weeks confirms the monumental scale of the assault on bird populations, commenting: "The statistics were staggering. Good Housekeeping reported in its winter of 1886-1887 issue: 'At Cape Cod, 40,000 terns have been killed in one season by a single agent of the hat trade.' On Cobb's Island along the Virginia Coast, an 'enterprising' New York businesswoman bagged 40,000 seabirds —at 40 cents apiece — to meet the demands of a single hat-maker." Doughty makes clear, in her study of feather millinery reported in Harper's Bazaar in the final decades of the nineteenth century, that not only exotic birds but also birds such as pigeons, domestic fowl, owls, and gulls decorated women's hats, dresses, collars, and fans.

of 1913, and the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, designed to protect migratory and song birds from the immediate threat of species extinction. Robin Doughty, in Feather Fashions and Bird Preservation cites numbers extracted from London auction sales between 1890 and 1911: 1,125,000 herons and egrets (1897-1911), 50,000 kingfishers (1906-1907), 152,000 hummingbirds (1904-1911), 155,000 birds of paradise (1904-1908), noting that, in 1888, "a single London dealer admitted that he had sold 2,000,000 of small birds of every kind and color" (30). Weeks confirms the monumental scale of the assault on bird populations, commenting: "The statistics were staggering. Good Housekeeping reported in its winter of 1886-1887 issue: 'At Cape Cod, 40,000 terns have been killed in one season by a single agent of the hat trade.' On Cobb's Island along the Virginia Coast, an 'enterprising' New York businesswoman bagged 40,000 seabirds —at 40 cents apiece — to meet the demands of a single hat-maker." Doughty makes clear, in her study of feather millinery reported in Harper's Bazaar in the final decades of the nineteenth century, that not only exotic birds but also birds such as pigeons, domestic fowl, owls, and gulls decorated women's hats, dresses, collars, and fans.

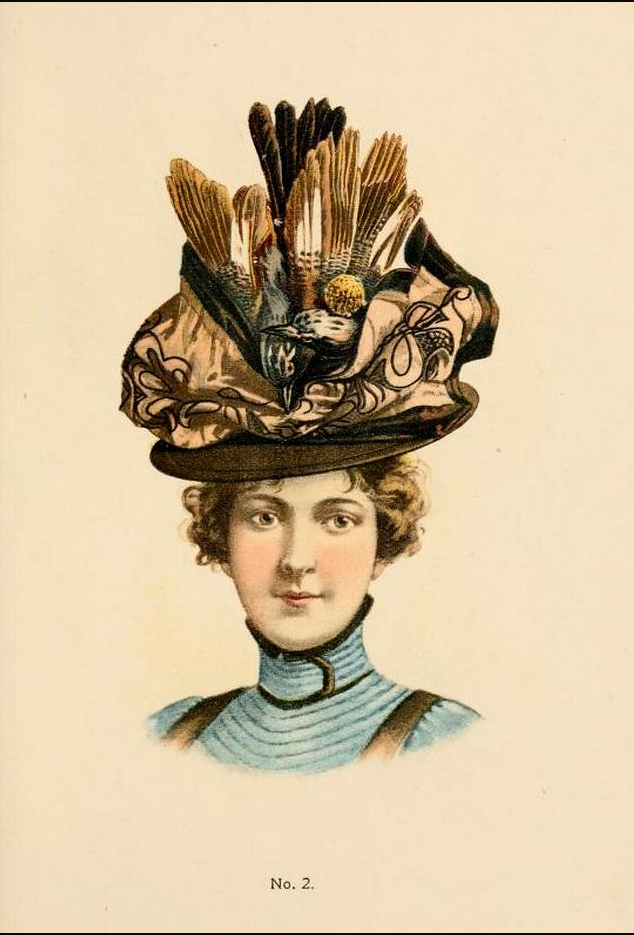

Anon. "No. 1." Hats by H O'Neill of New York 1899-1900.

A "war of extermination" waged against seabirds is the phrase used by William Dutchner in the article "Destruction of Bird-Life in the Vicinity of New York," published in the journal Science in 1886 (197). The extent of this fashion craze is reflected in Louisa May Alcott's description of childrens' dolls decorated with bird feathers. Two stories from the collection Lulu's Library (1889) are representative: in "Trudel's Seige" the protagonist is offered a "fine lady doll in pink silk, with a feather in her hat, and tiny shoes on her feet" (n.pag.); while the narrator of "Recollections of my Childhood" relates how "Needle-work began early; and at ten my skilful sister made a linen shirt beautifully, while at twelve I set up as a dolls' dressmaker, with my sign out, and wonderful models in my window. All the children employed me; and my turbans were the rage at one time, to the great dismay of the neighbor's hens, who were hotly hunted down that I might tweak out their downiest feathers to adorn the dolls' head-gear" (n.pag.).

In a note to the item cataloged as Hat ca. 1915 and designed by "Mme. Pauline" (download of which is prohibited), the Metropolitan Museum of Art comments: "The beauty of bird plumage - and its usefulness for human adornment - has been recognized throughout the course of civilization. In the history of Western fashion, no period stand [sic] out more for the abundance and variety of feather trimmings than that beginning around 1860 and continuing to World War I. Feather merchants combed the globe to obtain beautiful and exotic plumes and skins, and common feathers were dyed, processed, clipped, and assembled to supply the demand for novel and attractive trimmings. In this hat from the climax of that period, Madame Pauline, a milliner located in [the] Bedford-Stuyvesant area, makes a strong statement on the fascination with the use of birds and feathers. Not only is a full bird affixed to the front, but numerous bird wings are also applied all around to completely cover the sides of the crown. Growing public distaste and the resulting legislation combined with the trend for smaller and less ornate hats to eventually put a close on this chapter of fashion extravagance."

In a note to the item cataloged as Hat ca. 1915 and designed by "Mme. Pauline" (download of which is prohibited), the Metropolitan Museum of Art comments: "The beauty of bird plumage - and its usefulness for human adornment - has been recognized throughout the course of civilization. In the history of Western fashion, no period stand [sic] out more for the abundance and variety of feather trimmings than that beginning around 1860 and continuing to World War I. Feather merchants combed the globe to obtain beautiful and exotic plumes and skins, and common feathers were dyed, processed, clipped, and assembled to supply the demand for novel and attractive trimmings. In this hat from the climax of that period, Madame Pauline, a milliner located in [the] Bedford-Stuyvesant area, makes a strong statement on the fascination with the use of birds and feathers. Not only is a full bird affixed to the front, but numerous bird wings are also applied all around to completely cover the sides of the crown. Growing public distaste and the resulting legislation combined with the trend for smaller and less ornate hats to eventually put a close on this chapter of fashion extravagance."

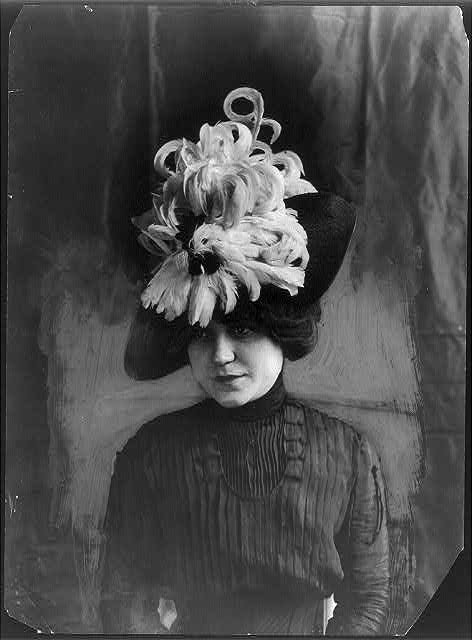

"Head and shoulders of model wearing 'Chanticleer' hat of bird feathers." ca. 1912. Library of Congress.

The public turn against the "bird craze" occurred within the context of the wider debate, in the final decades of the nineteenth century, concerning the very nature of femininity. Doughty reports of this debate: "The methods used to secure plumes, it was believed, should offend the sensibilities of city ladies accustomed to the Victorian norms of love, thoughtfulness and refinement, which were especially characteristic of the gentler sex" (63). The wearing of dead birds, with the implication of physical violence symbolized by taxidermied body parts, represented a stark contrast with the image of the "angel of the house" projected by elite women. Prominent Temperance and dress reform campaigner, Frances Willard (the first woman honored with a statue in the Rotunda of the national Capitol, see right), in How to Win: A Book for Girls (1886) highlights the hypocrisy of women who attend church while wearing dead birds on their hats: "for Christian Americans to go to church wearing a small flock of birdlings and piously listen to the sweet lesson, 'One of them shall not fall to the ground without your Father,' is a curiosity of cruelty for which no adequate explanation can by any possibility be furnished" (71).

The reasons why, in the name of fashion, women collaborated with these bloody trades was a question widely explored, for instance by the feminist reformer and sociologist Charlotte Perkins Gilman. She published, in 1915 in her journal The Forerunner, a series of 12 articles under the title "The Dress of Women." Like Willard, Gilman highlights the contrast between Victorian images of femininity and the violence of the mass killing committed by the fur and feather trades: “The worst pity of it is that it should be done by our women; tender mothers, emotional young girls, sensitive souls that are so grieved to see a horse beaten, a cat stoned, even a poor, staring-eyed mouse caught in one of those merciless wire-spring traps. It is for her that this agony is caused, and not for her need – only for her pleasure. … Would it not be reasonable for every woman of intelligence to determine once and for all, 'I will not decorate my body with death trophies' ” (Vol. VI, no. 8. August 1915, 215-216).  Continuing by asking why women embrace violent fashions, Gilman connects the lack of conscience that is required to wear "death trophies" with the denial to women of the full rights of citizenship: “the social conscience of women is not yet as keen as it will be when they realize their citizenship more fully. It is hard to waken a sense of co-responsibility in a subject class; a class not only held in tutelage, but isolated. We do not yet realize how the individual isolation of women, their close confinement in separate homes, their stringent responsibility to one man, to one family, and complete lack of civic relationships, has weakened the conscience of the world” (217).

Continuing by asking why women embrace violent fashions, Gilman connects the lack of conscience that is required to wear "death trophies" with the denial to women of the full rights of citizenship: “the social conscience of women is not yet as keen as it will be when they realize their citizenship more fully. It is hard to waken a sense of co-responsibility in a subject class; a class not only held in tutelage, but isolated. We do not yet realize how the individual isolation of women, their close confinement in separate homes, their stringent responsibility to one man, to one family, and complete lack of civic relationships, has weakened the conscience of the world” (217).

Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Suffrage demonstration in Union Square, New York. No date. Courtesy Schlesinger Library via Wikimedia Commons

The denial of civic participation, with the moral and ethical behaviors that implies, offers one explanation for women's subservience to the dictates of fashion. In an earlier publication, The Man-Made World: Or, Our Androcentric Culture (1911), Gilman offers a complementary explanation based on women's dependence on men: "Their condition, physical and mental, is largely abnormal, their whole passionate absorption in dress and decoration is abnormal, and they never looked, from a frankly human standpoint, at their position and its peculiarities, until the present age" (61). But the consequences of a refusal of this "abnormality" in respect to dress, in Gilman's experience, are far from positive: "in exact proportion as women grow independent, educated, wise and free do they become less submissive to men-made fashions. Was this improvement hailed with sympathy and admiration – crowned with masculine favor? The attitude of men toward those women who have so far presumed to 'un-sex' themselves is known to all. They like women to be foolish, changeable, always newly attractive; and while women must 'attract' for a living – why they do, that's all" (176). Gilman makes clear the connection between androcentrism and speciesism or patriarchy and carnism.

Criticisms of the intersecting patriarchal and carnist ideologies underlying women's fashion, articulated by reformers like Gilman and Willard, point to the incapacity of women to see the brutality of the fashion industry. Walter S. Weller refers to "criminally obtuse" women in his article "A Cruel Fashion," published in Food, Home and Garden (March 1899). "The Universal Leader, in an editorial on this subject says: 'If the members of the gentler sex could witness a thousandth part of the slaughter that takes place every month, that their patronage not only gives consent unto but commands, their awakened sensibilities would cry a halt, at least so far as they are personally responsible. ...' The editor of the above paper calls the ladies 'criminally obtuse' in persisting in this fashionable custom!" (89). They cannot see and do not care about the destruction and death that are necessary to provide the feathered decorations on their hats. Nor can they see the implications for their own position of the brutal sacrifice of birds and other beings to provide the feminine ornamentation that becomes, on the arm of a man, a patriarchal display of feminine property. Carol J. Adams has theorized this invisibility, in publications like The Sexual Politics of Meat (1990), as a rhetorical maneuver to which she refers as "the absent referent."  In the context of the dietary consumption of meat, Adams argues: “Behind every meal of meat is an absence: the death of the animal whose place the meat takes. The absent referent is that which separates the meat eater from the animal and the animal from the end product. The function of the absent referent is to keep our ‘meat’ separated from any idea that she or he was once an animal, to keep the ‘moo’ or ‘cluck’ or ‘baa’ away from the meat, to keep something from being seen as having been someone" (13).

In the context of the dietary consumption of meat, Adams argues: “Behind every meal of meat is an absence: the death of the animal whose place the meat takes. The absent referent is that which separates the meat eater from the animal and the animal from the end product. The function of the absent referent is to keep our ‘meat’ separated from any idea that she or he was once an animal, to keep the ‘moo’ or ‘cluck’ or ‘baa’ away from the meat, to keep something from being seen as having been someone" (13).

Anon. "Dressed to Kill: an Edwardian-era bird hat."

"Once the existence of meat is disconnected from the existence of an animal who was killed to become that ‘meat,’ meat becomes unanchored by its original referent (the animal), becoming instead a free-floating image, used often to reflect women’s status as well as animals’. Animals are the absent referents in the act of meat eating; they also become the absent referent in images of women butchered, fragmented, or consumable” (13). Animals are also the absent referents in the act of wearing feathered hats, boas, and brooches.

One of the effects produced by Martha Jane Anderson's poem, "The Bird Craze," is the raising of consciousness to the suffering of the creatures tortured and killed in the interests of fashion. The feminine protagonist is initially characterized as an impervious victim of fashion which, personified as "Dame Fashion," has the capacity to exert control over the thoughts and behavior of women. Caught in fashion's "sway" — a clever word choice that evokes at once bodily movement and ideological influence — she dons a Parisian hat that she knows will make “her friends admiringly start” (63). Her vanity is untouched by any complications such as ethics or morality, so the fact that the hat is adorned with the bodies of three songbirds does not affect her perception of  the hat as being especially charming and stylish: “A bonnet more charming could never be found / Though all the beau monde she should visit” (64). However, this impression is placed in tension by the values implicitly expressed by the poetic voice. While maintaining the stance of an observer, the speaker addresses the reader as "you," and embraces the reader as one part of a collective "we." The protagonist, however, remains at a distance as "her" or "she." Speaking directly to the reader, the narrator describes the ornamental, stuffed, birds as close to alive ("you could almost hear [them] humming") and attributes to them an emotive, romantic relation ("two dear little mates") linked to parenthood through the comparison of the hat with an "inverted nest" (63). The opening stanza animates the dead decorative birds, giving presence to the "absent referent," and this is developed in the subsequent stanzas. The suggestion that the protagonist might travel to other worlds ("all the beau monde") foreshadows the dream journey described in the three central stanzas. She is “transported, delight and thrilled” to the forests where the birds lived, and there she is forced to witness their violent slaughter: “But lo! fatal day, a behest to fulfill, / The huntsmen, with powder and ration / Came fully prepared the dear minstrels to kill, / To meet the demands of Dame Fashion” (64).

the hat as being especially charming and stylish: “A bonnet more charming could never be found / Though all the beau monde she should visit” (64). However, this impression is placed in tension by the values implicitly expressed by the poetic voice. While maintaining the stance of an observer, the speaker addresses the reader as "you," and embraces the reader as one part of a collective "we." The protagonist, however, remains at a distance as "her" or "she." Speaking directly to the reader, the narrator describes the ornamental, stuffed, birds as close to alive ("you could almost hear [them] humming") and attributes to them an emotive, romantic relation ("two dear little mates") linked to parenthood through the comparison of the hat with an "inverted nest" (63). The opening stanza animates the dead decorative birds, giving presence to the "absent referent," and this is developed in the subsequent stanzas. The suggestion that the protagonist might travel to other worlds ("all the beau monde") foreshadows the dream journey described in the three central stanzas. She is “transported, delight and thrilled” to the forests where the birds lived, and there she is forced to witness their violent slaughter: “But lo! fatal day, a behest to fulfill, / The huntsmen, with powder and ration / Came fully prepared the dear minstrels to kill, / To meet the demands of Dame Fashion” (64).

Anon. "No. 2." Catalogue, Hats by H. O'Neill of New York 1899-1900.

The birds' musical trilling turns to terrified screams that "pierced her heart with a meaning" that is an awakening to the violent truth of the fashions she has mindlessly consumed. The shocking truth of the bird trade exposed, the birds speak to her, appealing to her soul: “ ‘O indolent daughter of pleasure! / The pain that we suffer you must surely feel, / For justice will mete her full measure’ ” (64).  The narrator develops the point made by the birds. Justice, personified here and in conflict with "Dame Fashion," promises to avenge the spiritual injustice committed when humans usurp the power to end a life, which belongs only to God. The birds warn that this destruction of innocent life will be met with “full compensation” or retribution by God, evoking the biblical plagues of Egypt: "For blight and destruction shall rest on the land / And insects make great devastation." Conscious now of the truth of her dream-vision, the protagonist vows that “The forfeit of life shall ne’er yield me bliss, / May it never, O, never be broken! / My sisters, who thoughtlessly yield to caprice, / Let us live for some nobler endeavor, / And weave for our brows the fair laurels of peace, / And banish the bird-craze forever” (65). The once charming hat, with its "coronet" evoking a royal crown, has become a bonnet of death that will be replaced with "laurels of peace" as the lady works towards "some nobler endeavor" than the "mental distraction" previously offered by fashion. The poem appeals to the concept of femininity as allied with feelings and spirit more than reason. Emotion initially prompts the protagonist to don the hat, anticipating with a "thought that filled her whole heart" the envy of her friends upon beholding the fashionable Parisian bonnet. Later, the birds use a similar appeal to emotion — they "spoke to her soul" — to press their argument for equal rights. This equality is based on the equal capacity to experience pain: "The pain that we suffer you must surely feel" (64). The poem promotes equality between the human and the avian by attributing to the birds' creation of music the human term, "minstrels"; by characterizing the human protagonist as a "creature" ("This creature of taste," 64); and by endowing both the human and avian characters with direct, quoted, tagged speech.

The narrator develops the point made by the birds. Justice, personified here and in conflict with "Dame Fashion," promises to avenge the spiritual injustice committed when humans usurp the power to end a life, which belongs only to God. The birds warn that this destruction of innocent life will be met with “full compensation” or retribution by God, evoking the biblical plagues of Egypt: "For blight and destruction shall rest on the land / And insects make great devastation." Conscious now of the truth of her dream-vision, the protagonist vows that “The forfeit of life shall ne’er yield me bliss, / May it never, O, never be broken! / My sisters, who thoughtlessly yield to caprice, / Let us live for some nobler endeavor, / And weave for our brows the fair laurels of peace, / And banish the bird-craze forever” (65). The once charming hat, with its "coronet" evoking a royal crown, has become a bonnet of death that will be replaced with "laurels of peace" as the lady works towards "some nobler endeavor" than the "mental distraction" previously offered by fashion. The poem appeals to the concept of femininity as allied with feelings and spirit more than reason. Emotion initially prompts the protagonist to don the hat, anticipating with a "thought that filled her whole heart" the envy of her friends upon beholding the fashionable Parisian bonnet. Later, the birds use a similar appeal to emotion — they "spoke to her soul" — to press their argument for equal rights. This equality is based on the equal capacity to experience pain: "The pain that we suffer you must surely feel" (64). The poem promotes equality between the human and the avian by attributing to the birds' creation of music the human term, "minstrels"; by characterizing the human protagonist as a "creature" ("This creature of taste," 64); and by endowing both the human and avian characters with direct, quoted, tagged speech.  The poem concludes with the words of the protagonist who now expresses a morality that is consonant with that of the poetic speaker and the birds with whom the poetic voice has been aligned throughout. Having experienced an awakening to the truth of fashion and the economies of violence on which it depends, the protagonist now speaks to her "sisters, who thoughtlessly yield to caprice" (65), and calls them to political action inspired by the reality of the absent referent.

The poem concludes with the words of the protagonist who now expresses a morality that is consonant with that of the poetic speaker and the birds with whom the poetic voice has been aligned throughout. Having experienced an awakening to the truth of fashion and the economies of violence on which it depends, the protagonist now speaks to her "sisters, who thoughtlessly yield to caprice" (65), and calls them to political action inspired by the reality of the absent referent.

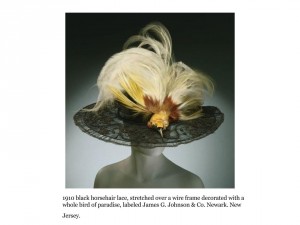

Anon. "1910 black horsehair lace, stretched over a wire

frame decorated with a whole bird of paradise, labeled

James G. Johnson & Co. Newark. New Jersey."

Martha Jane Anderson, "The Bird Craze" (1895)

Mount Lebanon Cedar Boughs: Original Poems by the North Family of Shakers, ed. Anna White. Buffalo: Peter Paul Book Co., 1895. 63-64.

[63]

THE BIRD CRAZE.

A WOMAN whom fashion long held in her sway,

Whose vanity naught could embarrass,

Was decked in rich silks and velvets all gay,

And a beautiful bonnet from Paris.

A head-dress, you know to the feminine mind

Is the principal point of attraction,

A part of adornment we frequently find

That causes a mental distraction.

And here was the thought that filled her whole heart,

The style was so sweet and becoming,

She knew that her friends would admiringly start,

For the birds, you could almost hear humming.

Two dear little mates decked the front of the crest,

With plumage the brightest and fairest,

And over the crown — like an inverted nest —

Spread wings of a songster the rarest.

[64]

The ribbons that folded the coronet round

Gave a touch and a grace most exquisite,

A bonnet more charming could never be found

Though all the beau monde she should visit.

A change wrought by magic, comes over our theme,

Which causes a simple digression,

This creature of taste had a wonderful dream

Which made on her mind an impression.

She seemed to be dressed a la mode — cap-a-pie,

For Sol's blessed southland preparing,

A journey most pleasant new beauties to see,

Where nature a glad smile is wearing;

She was there, transported, delighted and thrilled

For forests and groves were most charming,

Where sunny-hued songsters their blithe music trilled,

No terror their wild haunts alarming.

But lo! fatal day, a behest to fulfill,

The huntsmen, with powder and ration

Came fully prepared the dear minstrels to kill,

To meet the demands of Dame Fashion.

Quick came the reports, and they fell to the ground

Like innocent victims in battle,

In the midst of the slaying our dreamer was found

Transfixed with the din and the rattle.

The birds flew around her and screamed in their fright

Till their cries pierced her heart with a meaning

And turned into sorrow her days of delight

The truth of the vision unscreening.

They spoke to her soul with a plaintive appeal

"O indolent daughter of pleasure!

The pain that we suffer you surely must feel,

For justice will mete her full measure."

All over the tropics, from sun unto sun

The vandals are scouting and raiding,

And thousands of birdlings are slain one by one,

Such cruelty God is upbraiding.

[65]

This work of destruction by unhallowed hands,

Shall meet with a full compensation,

For blight and destruction shall rest on the land,

And insects make great devastation.

She nodded her head: from dreamland awoke,

But the vision she knew must be real,

A horror her head-dress now seemed to invoke

In the light of a humane ideal.

She said, "I have learned a deep lesson from this,

A vow I will make as a token,

The forfeit of life shall ne'er yield me bliss,

May it never, O, never be broken!

My sisters, who thoughtlessly yield to caprice,

Let us live for some nobler endeavor,

And weave for our brows the fair laurels of peace,

And banish the bird-craze forever."

REFERENCES and FURTHER READING

Adams, Carol J. The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory. 20th Anniversary Edition. 1990; New York & London: Continuum, 2010.

---. "The War on Compassion." Antenna issue 14 ( Autumn 2010): 5-11.

Alcott, Louisa May. Lulu's Library. Vol. 3. Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1889.

Allen, J. A. "The Present Wholesale Destruction of Bird-Life in the United States." Science Vol. 7 (new series), Issue 160s (1886): 191-195.

American Humane. "History." AmericanHumane.org. 2023.

Anderson, Martha Jane. “The Bird Craze.” Mount Lebanon Cedar Boughs: Original Poems by the North Family of Shakers. Buffalo: Peter Paul Book Co., 1895. 63-64. Text scanned by Google and corrected by Deborah Madsen against the photographed images at Hathi Trust.

Birdsall, Amelia. A Woman's Nature: Attitudes and Identities of the Bird Hat Debate at the Turn of the 20th Century. Senior Thesis. Haverford College History Department, 2002.

Doughty, Robin W. Feather Fashions and Bird Preservation: A Study in Nature Protection. Berkeley; University of California Press, 1975.

Dutcher, William. "Destruction of Bird-Life in the Vicinity of New York." Science 160s (1886): 197-199.

Gephart, Emily & Michael Rossi. "How to Wear the Feather: Bird Hats and Ecocritical Aesthetics." Maura Coughlin and Emily Gephart, eds. Ecocriticism and the Anthropocene in Nineteenth-Century Art and Visual Culture. New York: Routledge, 2019. 192-207.

Gilman, Charlotte Perkins. "The Dress of Women." The Forerunner Vol. VI, no. 8 (August 1915): 215-220.

Lasky, Kathryn. She's wearing a dead bird on her head. Westport, CT: Hyperion, 1995.

Merchant, Carolyn. "Women of the Progressive Conservation Movement: 1900–1916." Environmental Review Vol. 8, no. 1 (Spring 1984): 57-85.

Moore-Colyer, R. (2000). "Feathered Women and Persecuted Birds: The Struggle against the Plumage Trade, c. 1860–1922." Rural History Vol. 11, no. 1 (2000): 57-73.

Patchett, Merle. "The Biogeographies of the Blue Bird-of-Paradise: From Sexual Selection to Sex and the City." Journal of Social History Vol. 52, Issue 4 (Summer 2019): 1061-1086.

Scarborough, Amy D. Fashion media's role in the debate on millinery and bird protection in the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. PhD dissertation, Oregon State University, 2009.

Smith, Malcolm. Hats: A Very UNnatural History. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2020.

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. "Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918." Full-text of the Act.

Weeks, Linton. "Hats Off To Women Who Saved The Birds." NPR History Dept. 15 July 2015.

Weller, Walter S. "A Cruel Fashion." Food, Home and Garden Vol. III, New Series, no. 26 (March 1899): 48.

Willard, Frances. How to Win: A Book for Girls. New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1886.

IMAGE CREDITS

Anon. "1910 black horsehair lace, stretched over a wire frame decorated with a whole bird of paradise, labeled James G. Johnson & Co. Newark. New Jersey." Jeanmarie Tucker, "The Bird Hat: 'Murderous Millinery'. " Maryland Center for History and Culture, no date.

Anon. "The Bird on Nellie's Hat." 1906. In Harmony: Sheet Music from Indiana. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Anon. "Dressed to Kill: an Edwardian-era bird hat." Hayley Webster & Gemma Steele, "Flight of Fashion: When Feathers Were Worth Twice their Weight in Gold." Museums Victoria, no date.

Anon. "Martha Jane Anderson." Shaker Museum. Copyright of this artwork: "You are welcome to reproduce low resolution images of objects from the Shaker Museum collection for your personal, non-commercial, and / or academic use."

O'Neill, H. & Co. (New York, N.Y.). Fine millinery: fall and winter styles for ladies, misses and children, 1899-1900. Catalog. New York: The Company, 1899.

Bain News Service. "Head and shoulders of model wearing 'Chanticleer' hat of bird feathers." ca. 1912. George Grantham Bain Collection. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Digital ID: cph 3b08931 //hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3b08931. No known restrictions on publication.

CPGilman--courtesy-schlesinger-libraryj. "Suffrage demonstration in Union Square(NY)." Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Knox, designer. "Mourning hat ca. 1895."Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Mrs. Robert S. Kilborne, 1958. Accession Number: 2009.300.1960. Restricted Access. No enlargement, no full-screen view, nor download permitted. NOTE: "Though entrenched in a mourning period, women of quality remained stylishly adorned. This beautiful example by one of the premiere American hatters of the 19th century is a highly dramatic hat. The forward-perching silhouette along with the extreme popularity of feathers and birds at this time make this hat an excellent example of the 1890s style."

Library of Congress. "North Family, 202 Shaker Road, New Lebanon, Columbia County, NY." Photos from Survey HALS NY-7.

Mérshon, Estelle, designer. "Hat ca. 1910." Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Amelia Beard Hollenback, 1966. Accession Number: 2009.300.1564. Restricted Access. No enlargement, no full-screen view, nor download permitted. NOTE: "Amelia Beard Hollenback (1844-1918) was the wife of prominent financier and philanthropist John Welles Hollenback (1835-1927). As the lines of fashionable clothing began to become sleeker and simpler in the period after 1908, millinery responded with simpler but highly dramatized designs. This hat employs effects typifying the period - impressive size, asymmetrically turned-up brim, contrasting color facing, and trim of limited material but strong presence and space-expanding lines - to achieve its great sense of drama, high glamour and style. The typical oversize crown served to coordinate proportionally with the large hairstyles of the period. The wings used are most probably gull, which was noted at the time as being particularly desirable."

Mlle. Louise, designer. "Hat ca. 1890." Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Pratt Institute, 1943 Accession Number: 2009.300.1777. Public Domain. Open Access.

Mme. Pauline, designer. "Hat ca. 1915." Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Mrs. Frederic G. McMahon in memory of her grandparents, Mr. and Mrs. Gilbert C. Halsted, 1975. Accession Number: 2009.300.2180. Restricted Access. No enlargement, no full-screen view, nor download permitted.

RadioFan. "Statue of Frances Willard in the US Capitol." English Wikipedia. CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Last updated on March 29th, 2023

SNSF project 100015_204481

@VLS@veganism.social | VeganLiteraryStudies | @veganliterarystudies | @vegan_lit_studies

How to cite this page:

Madsen, Deborah. 2023. "Ethical Veganism, Fashion Victims, and the Victorian 'Bird Craze'." Vegan Literary Studies: An American Textual History, 1776-1900. <Date accessed.> <https://www.unige.ch/vls/anthology/anderson>.