Permanent damage after brain inflammation

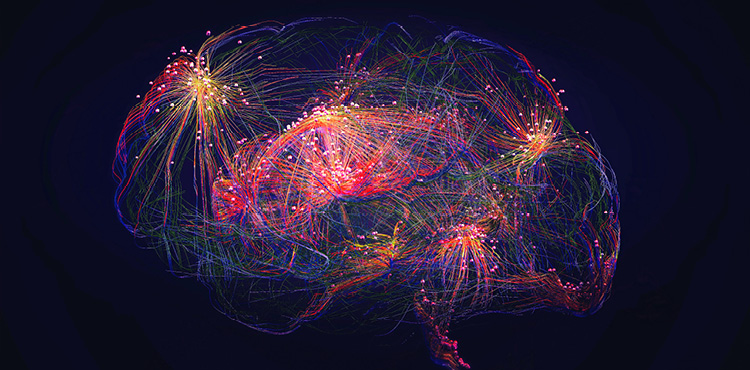

© iStock

A team from UNIGE has demonstrated that inflammation triggered by an immune response causes lasting epigenetic remodeling and altered synaptic function of neurons, explaining the persistent neurological symptoms seen after encephalitis. These surprising findings are published in the journal Neuron.

Encephalitis is an inflammation of the brain that can be caused by infections or autoimmune reactions. Beyond the acute phase, a significant proportion of patients may suffer from lasting neurological disorders, including memory deficits, seizures or cognitive impairment. "Why did these symptoms often persist long after the inflammation itself had resolved? That's what we wanted to find out", says Doron Merkler, professor in the Department of Pathology and Immunology and at the Centre for Inflammation Research at UNIGE Faculty of Medicine.

Irreversible molecular changes

Using a mouse model of viral encephalitis and advanced molecular tools, the research team was able to track the complete trajectory of epigenetic and transcriptional changes in neurons, from the acute to the chronic phase of the disease.

"We discovered that during encephalitis, immune cells can leave a lasting 'molecular scar' in neurons", explains Doron Merkler.

Specifically, a molecule released by immune cells during the inflammatory response, called interferon-gamma (IFNγ), triggers long-term change in how neurons regulate their genes that, without killing them, permanently alters their synaptic connections.

"Neurons exposed to an immune attack undergo persistent changes in their genetic regulation", says Ghazal Shammas, a former PhD student in Doron Merkler's laboratory and first author of the study. "These changes reduce the activity of genes necessary for proper synaptic function, leading to long-term disruption of brain circuits, even after the immune response has ended."

The same mechanism in the human brain

The research team observed similar changes in gene expression in the brain tissue from people with Rasmussen's encephalitis, a rare but serious human brain disease. This suggests that the mechanism identified in mice is also relevant to human disease.

Overall, this work helps explain why brain inflammation can cause permanent neurological damage without necessarily inducing neuron death. It highlights a previously unrecognised role of immune signalling in reprogramming neurons at a molecular level and opens new avenues for therapies aimed at protecting or restoring synaptic function in chronic neuroinflammatory conditions.